U.S. President James Polk declared war on Mexico on May 13, 1846, and Col. Stephen W. Kearny’s Army of the West crossed into Mexican Territory on August 2, 1846, on his way to set up a civil government with Charles Bent at its head. On August 8, 1846, he was camped on the Rio Colorado (probably Canadian River) and gave his first orders in New Mexico.

(Library of Congress.)

Following the old Santa Fe road, according to William H. Emory (98) through Las Vegas to Santa Fe, General Kearny declared that “By the annexation of Texas, the Rio Grande from its mouth to its source has become the boundary between the United States and Mexico, consequently all persons living on the East side of that river are to be regarded as Citizens of the former and are to be treated accordingly…We are taking possession of a Country and extending the laws of the United States over a population who have hitherto lived under widely different ones, and humanity as well as policy requires that we should conciliate the inhabitants by kind and courteous treatment.”

The settlers of Rio Colorado were now under American control. But what the citizens of Rio Colorado wanted and needed was relief from the Indian attacks on their livestock, houses, and crops. Kearny promised to provide some help here. He ordered that “The inhabitants of this Country must be protected from the Indians, and for that purpose several companies of Mounted Volunteers must be kept near the frontier. If the Indians after agreeing to a peace will not keep it, a large force (sufficient to insure entire and complete success) should be marched into their country for their punishment” (99). Soon afterward on September 16th, Kearny ordered Major Clark to “…detach 50 mounted men of his command, under Capt. Fischer, with orders to proceed without delay to the Apache Country for the purpose of recovering property stolen within a few days past by these Indians from the frontier inhabitants.”

But the problems with the Indians continued to increase. On October 2, Kearny invited the chief of the Navajos to Santa Fe “…for the purpose of holding a Council, and making peace between them and the inhabitants of New Mexico (now forming a party under protection of the U. States) and as they have promised to come, but have failed doing so, and instead …continue killing the people committing depredations upon their property, it becomes necessary to send a military expedition into the country of these Indians to secure a Peace and better conduct from them in the future.”

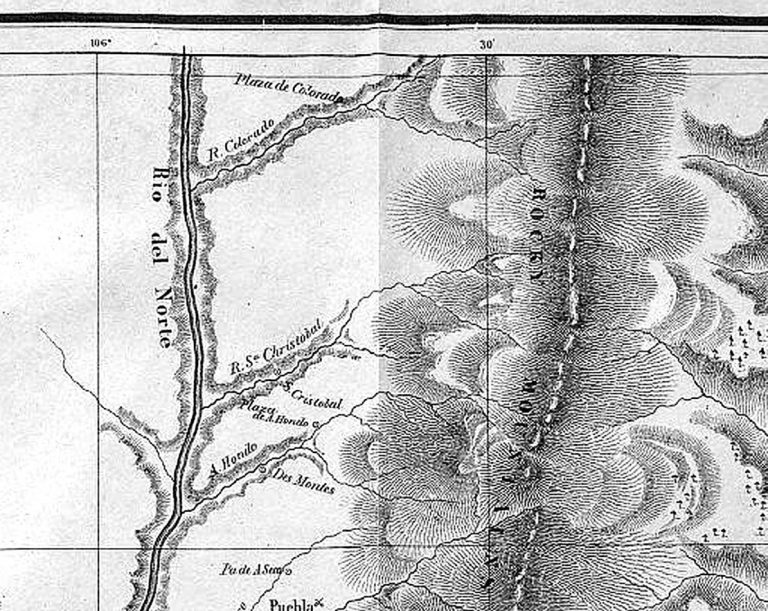

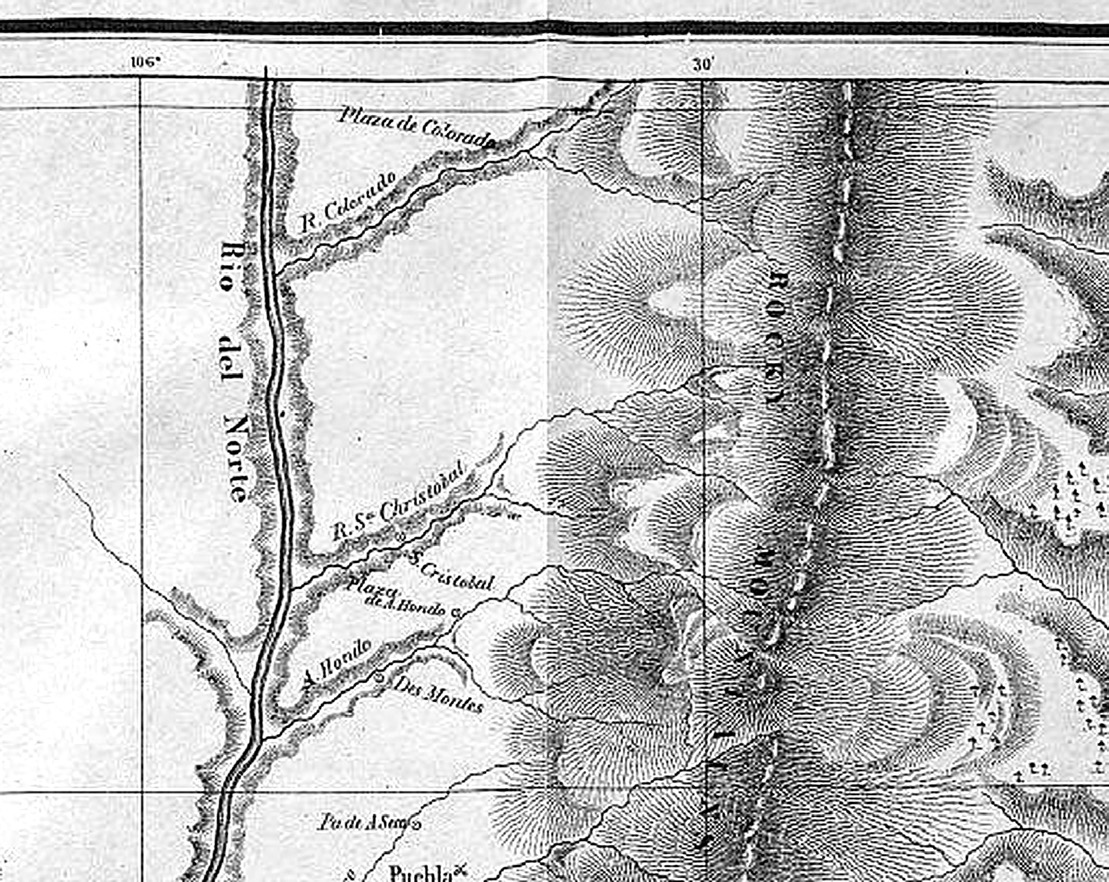

Kearny sent Col. Alexander Doniphan to march into Navajo country to the west of Santa Fe. “He will cause all the Prisoners and all the Property they hold which may have been stolen from the Inhabitants of the Territory of New Mexico to be given up and he will require from them such security for their future good conduct as he may think ample and sufficient by taking hostages or otherwise.” Lieut. W.H. Emory, an Army topographer accompanying Kearny provided a detailed journal of the entire expedition and also produced the first accurate map of the New Mexican territory, including the Rio Colorado of the Questa area (100).

Kearny himself did not stay long in New Mexico. His sights were on California, and after he established a civil government in the New Mexico Territory and instituted a new legal code, he left for California on Septmber 25th, 1846. Kearny was injured at the Battle of San Pasqual. He served as military governor of California Territory after a bitter disagreement with Lt. Col. John Fremont over who should lead the new territory. Fremont, who will appear again in our story, was court-martialed for his role in the California fiasco, although he was eventually pardoned by President James K. Polk. Kearny was hit hard by his dispute, and succumbed to a tropical disease on his way home in 1848 (101).

Meanwhile in northern New Mexico, a company of the First Dragoons was stationed at Taos to defend this portion of the Ninth Military Department organized in 1848, and much attention was given to the Navajos who were raiding from Abiquiu to Albuquerque. Peace treaties were made and broken several times over (102). But the depredations on the Rio Colorado settlers on the northernmost frontier continued.

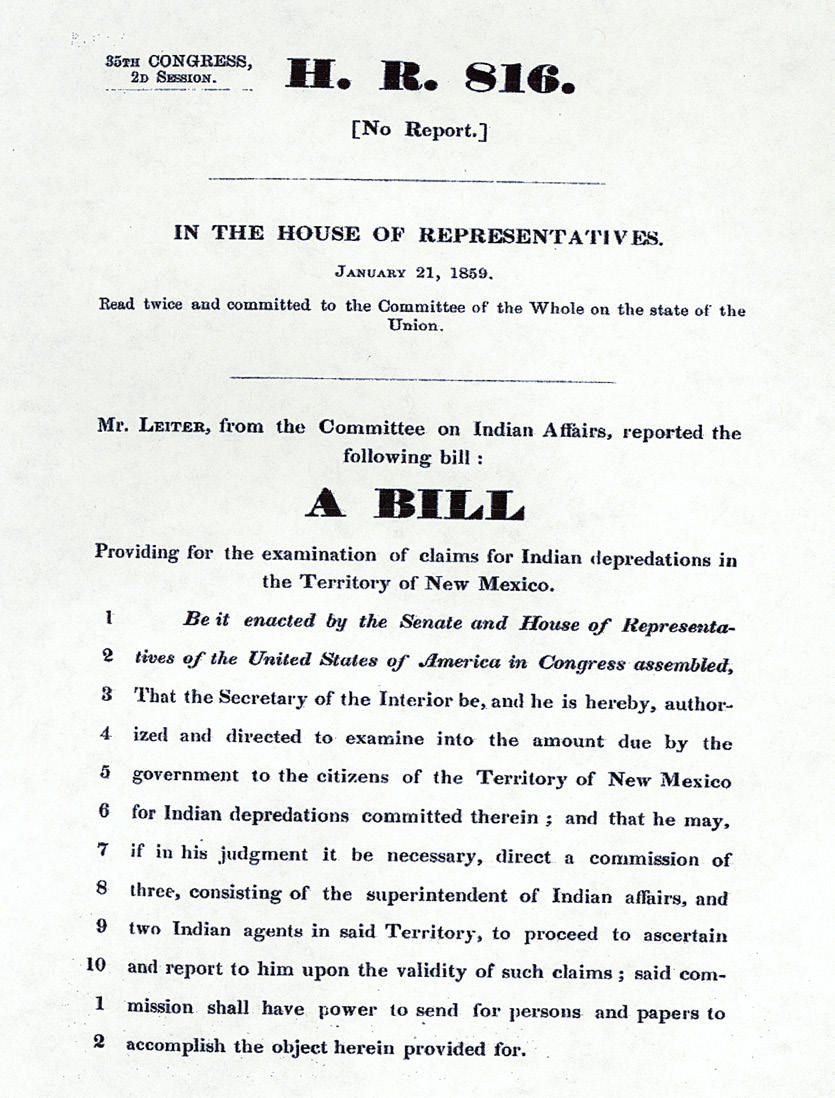

To give an idea of the level of damage the Indians raids were inflicting, according the the reports of the U.S. Marshals during the period from August 1, 1846 to October 1, 1850, property stolen by the Apaches in New Mexico alone amounted to 12, 887 mules, 7050 horses, 31,581 horned cattle, and 453,293 head of sheep (103). Protecting against these raids proved costly for the U.S. federal government, which spent $12 million between 1848 and 1853 in the Ninth Military Department for defense against the Indian raids.

American interest in this new addition to the United States was growing by the late 1840s, as evidenced by articles appearing in the national magazines, such as The American Whig Review. A November 1848 article (104) provides a very detailed picture of life in this region. The Comanches and Apaches, still terrorizing Rio Colorado, are described as being “…wild and predatory, and having now the use of horses, may be regarded as the Arabs of the elevated deserts of the New World…” and that they “…are exceedingly warlike, and constitute the chief and most dangerous obstacle to the passage southward of the traders and settlers….” The Navajos, who occupy “…the country between the upper waters of the Del Norte and the Sierra Anahuac, and perhaps extending toward Colorado…are half-agricultural, and not less martial than the Apaches, who speak the same language with them….”

The incursions on the northern New Mexico frontier were also now well known—“These Indians…are animated by the most intense hatred of the Mexicans. They have completely depopulated some portions of the frontiers of the Mexican States. The upper half of the valley of the Rio Grande is constantly subject to their incursions. One of the chiefs of a party of these Indians met, by appointment, by General Kearny, exclaimed as the latter was about proceeding from the rendezvous, ‘You have taken New Mexico, and will soon take California; go then and take Chihuahua, Durango, and Sonora; we will help you. You fight for land; we care nothing for land; we fight for the laws of Montezuma and for food. The Mexicans are rascals; we hate them all.’” Later in this piece, the Navajos are described as being “…almost constantly at war with the Mexicans. They have had some skirmishes with American trappers, which resulted much to their disadvantage, and of whom they stand in considerable awe.”

(Library of Congress.)

A survey by the U.S. Army in 1850 indicated that the line to be defended against the Indians was from Abiquiu to Rio Colorado to Rayado, La Junta, Las Vegas, and San Miguel (105). Obviously Rio Colorado was right on the front lines in this respect, but no military post was recommended for the village. Rayado and Taos housed the closest garrisons. The U.S. troops were described by Twitchell (106) as “…a degenerate military mob, open violators of law and order, and …they daily heaped injury and insult upon the people…”. As a result, trouble between the soldiers and the Mexican locals frequently erupted.

The resentment of the local Spanish population and the Indians against the incursions of the Anglos finally reached its peak in the 1847 Taos Rebellion. The Mexicans and Indians of Taos joined forces on January 19, 1847 and killed all who sided with the United States, including New Mexico Governor Charles Bent, the Sheriff of Taos, Stephen Luis Lee, and the Americans at Turley’s Mill (January 20, 1847) north of Taos (107). All of the towns in northern New Mexico, including Rio Colorado, joined the insurrection. John Albert and William LeBlanc, who had escaped from Turley’s Mill, headed north to Fort Pueblo. They later explained that they escaped death by avoiding Rio Colorado. Tom Tobin escaped from Turley’s Mill and rode south to Santa Fe to bring news of the uprising. Other mountain men, including Tobin’s brother Charles Autobees also fled to the relative safety of Santa Fe (108).

But two other escapees from Turley’s Mill—William Harwood and Mark Head—were not so lucky. Later George Ruxton learned more about this attack, most likely from John Albert after he reached Fort Pueblo, and describes their murder in Rio Colorado and Laforet’s role in these events. Here is his account (96):

“As Markhead [Mark Head] and Harwood would have arrived in the settlements about the time of the rising, little doubt remained as to their fate, but it was not until nearly two months after that any intelligence was brought concerning them. It seemed that they arrived at the Rio Colorado, the first New Mexican settlement, on the seventh or eighth day, when the people had just received news of the massacre in Taos. These savages, after stripping them of their goods, and securing, by treachery, their arms, made them mount their mules under the pretence of conducting them to Taos, there to be given up to the chief of the insurrection. They had hardly, however, left the village when a Mexican, riding behind Harwood, discharged his gun into his back: Harwood, calling to Markhead that he was “finished,” fell dead to the ground. Markhead, seeing that his own fate was sealed, made no struggle, and was likewise shot in the back by several balls. They were then stripped and scalped and shockingly mutilated, and their bodies thrown into the bush by the side of the creek to be devoured by the wolves. They were both remarkably fine young men.

Laforey, the old Canadian trapper, with whom I stayed at Red River, was accused of having possessed himself of the property found on the two mountaineers, and afterwards of having instigated the Mexicans to the barbarous murder. The hunters on Arkansa vowed vengeance against him, and swore to have his hair some day, as well as similar love-locks from the people of Red River. A warexpedition was also talked of to that settlement, to avenge the murder of their comrades, and ease the Mexicans of their mules and horses.”

The Taos Rebellion was put down by Colonel Sterling Price and an army of 353 men who came up from Santa Fe (109). The final battle took place at the church at Taos Pueblo, in which 150 Indians and Mexican sympathizers were killed. The survivors were tried at the first term of the American Court in Taos, Carlos Beaubien Presiding Judge (whose son Narciso was killed in the uprising), and executed in Taos. The Trials were held from April 5 through the 24th , 1847; 15 of 17 men were tried and convicted of murder and executed by hanging, 5 were tried and one (Antonio Maria Trujillo) was convicted, and 6 of 17 were tried and convicted of larceny. Pablo Montoya, the leader of the uprising had been executed on February 7th. According to Lewis Garrard, he was “…hung the next day by drumhead court martial in the plaza of San Fernandez.” (110–112). Although the names of all of the men tried are given in the Court records, their towns of residence are not given, so it is not clear whether any of the plotters from Rio Colorado received this rough justice.

The next year, on a trip from Los Angeles to Taos and then Santa Fe with Kit Carson, George D. Brewerton describes an encounter with Indians that are camped about a day’s journey north of Taos, which would be in the Rio Colorado area. “…a sudden turning of the trail brought us into view of nearly two hundred lodges…” Carson hoped that these Indians were “Eutaws,” which he considered “a friendly tribe.” They were not Eutaws and Carson and his party used subterfuge to avoid an initial attack; the Indians soon caught up with them and were on the verge of attacking Carson’s party when word came that a party of 200 American volunteers were on their way “…to punish the perpetrators of recent Indian outrages in that vicinity….” Brewerton and Carson and their companions reached the northernmost Mexican dwelling, “This town being nothing more than a collection of shepherd’s huts, we did not enter but made camp near it.” “I remember celebrating this occasion,” Brewerton wrote, “by visiting one of the Mexican huts, where I ordered the most magnificent dinner that the place afforded, eggs and goat’s milk….” The settlement described by Brewerton could very well have been Rio Colorado (113).

Notes

98. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Lieutenant Emory reports; a reprint of Lieutenant W.H. Emory’s notes of a military reconnaisaance. Intro and notes by Ross Calvin. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1951.

99. U.S. Army of the West. Orders issued by Brig. Gen. Stephen W. Kearny and Brig. Gen. Sterling Price to the Army of the West, 1846-1848, Order no. 30, September 23, 1846. LC SW 978.904 K245.

100. U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Lieutenant Emory reports; a reprint of Lieutenant W.H. Emory’s notes of a military reconnaisaance. Intro and notes by Ross Calvin. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1951.

101. General Stephen Watts Kearny. Rip.physics.umk.edu/Kearny/SWK.html, accessed 11/9/02.; Roberts, Phyllis. Stephen Watts Kearny. Buffalo Country Historical Society, Buffalo Tales 2(1): January 1979. Bchs.kearney.net/Btales_197901.htm, accessed 11/9/02; Senate Executive Journal, August 9, 1848. A Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774-1875. Library of Congress, memory.loc.gov.

102. Bender, A.B. Frontier defense in the Territory of New Mexico, 1846–1853. New Mexico Historical Review, vol. IX, no. 3, July 1934, pp. 249-272.

103. Bender, A.B. Frontier defense in the Territory of New Mexico, 1846–1853. New Mexico Historical Review, vol. IX, no. 3, July 1934, pp. 249-272.

104. New Mexico and California: The ancient monuments and the aboriginal, semi-civilized nations of New Mexico and California, with an abstract of the early Spanish exploitations and conquests in these regions, particularly those now falling within the Territory of the United States. The American Whig Review 8(5): November 1848. memory.loc.gov, accessed 6/27/02.

105. McCall, Col George Archibald. New Mexico in 1850: A Military View. Robert W. Frazier (ed.). University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

106. Twitchell, Ralph E. The Leading Facts of New Mexico History. Horn & Wallace, Albuquerque, 1963, vol III pp 229-263.

107. Murphy, Lawrence R. The United Staters Army in Taos, 1847–1852, New Mexico Historical Review XLVIII, no. 1, January 1972, pp. 33-48.

108. Perkins, James E. Tom Tobin Frontiersman. Herodotus Press, Pueblo West, CO, 1999.

109. Murphy, Lawrence R. The United Staters Army in Taos, 1847-1852, New Mexico Historical Review XLVIII, no. 1, January 1972, pp. 33-48.

110–111. Cheetham, Francis T. The first term of the American Court in Taos, New Mexico. The New Mexico Historical Review, vol. 1, no. 1, January 1926, pp. 23-41.

112. Garrard, Lewis H. Wah-to-yah and the Taos Trail. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1955.

113. Brewerton, George D. A ride with Kit Carson through the Great American Desert and the Rocky Mountains. Harpers New Monthly Magazine II (39). Corneel University Making of America series, cdl.library.cornell.edu, accessedd 5/18/03.