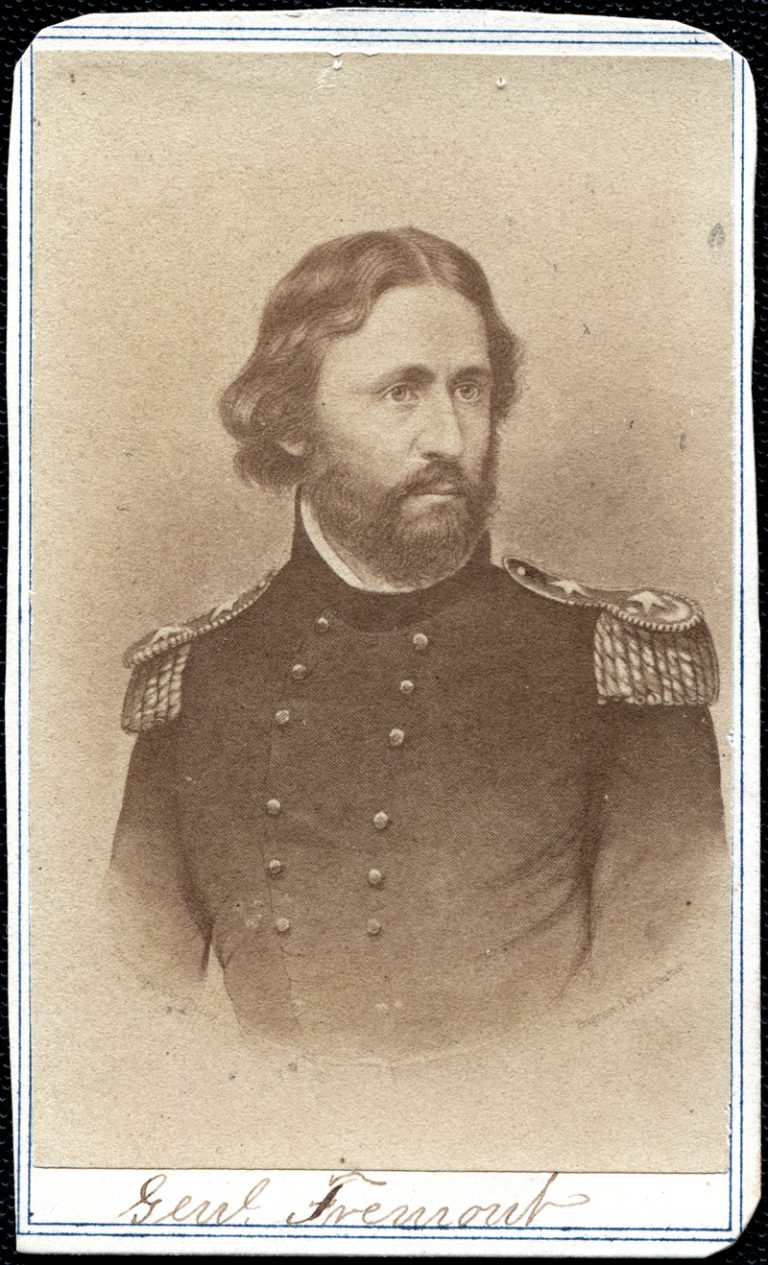

The outside world from the east arrived in Rio Colorado in a big way with the fourth expedition of “The Pathfinder,” John Charles Fremont. Commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant of the Topographical Engineers of the U.S.Army, and later as Captain, Fremont had previously led expeditions to explore the unknown regions of the West for the War Department of the U.S. government. (114).

Fresh from his stinging court martial over the Bear Revolution in California, Fremont, now on his own and financed by St. Louis merchants, set out in October of 1848 with 33 or so men, one-third of them greenhorns and the remainder veterans of previous expeditions, and 120 mules to find a passage to California through the upper waters of the Rio Grande that might be suitable for a railroad. He decided to make the trip during the winter to demonstrate that the railroad could operate year round. The mountain man Dick Wootten refused to guide Fremont because “There is too much snow ahead for me (115).

Fremont finally persuaded “Old Bill” Williams, who was in Pueblo, Colorado, to guide the party through the mountains—although “…it was not without some hesitation that he consented to go, for most of the old trappers at the Pueblo declared that it was impossible to cross the mountains at that time, that the cold upon the mountains was unprecedented and the snow deeper than they had ever known it so early in the year.” (116). Another French trapper, Longe, turned back at Pueblo because of the snow and cold and warned that there would be “evil to those who continued” (117). The winter turned out to be a particularly brutal one and the expedition foundered in the 18-foot-deep snows (118) of the La Garita Mountains, north of what is now Del Norte,Colorado (118). The mules began to die from the cold, and the men had to cut down trees for firewood, build sleds to carry their equipment, and to make paths in the snow. (Evidence of these camps still exists and the cut off tree stumps, showing the depth of the snow, can be seen at several sites, including the famous Christmas camp site.)

Thomas Martin, one of the expedition members, described their situation—“Our path or track was sunk down deep in the now in places 18 feet deep, quite wide at the top but gradually narrowing until at the bottom it was only a foot wide. We made no other attempt with the mules. The two we took over froze to death 4 days later. At the first camp we left nearly 100 mules that all perished, with either cold or hunger…..Seeing that we could not get the mules over we returned and packed all our bags over on our backs to our new camp.”

Fremont decided to send a rescue party on December 26th to the New Mexican villages to obtain food and supplies and help in moving his men from their camp. “In this situation, I determined to send in a party to the Spanish settlements of New Mexico for provisions and mules to transport our baggage to Taos…..we had not two week’s provisions in the camp. These consisted of a store which I had reserved for a hard day, macaroni and bacon” (119).

They estimated that the closest settlement was Rio Colorado and a party of four men, including the famous Old Bill Williams, set off with $1800 to find help. (132). Making their way down the mountains to the San Luis Valley, the party bogged down in the snow and cold and from lack of food and fear of Indian attacks. When they did not return to the camp in the La Garitas by January 11th, Fremont and another party went after them. Fremont wrote, “After sixteen days had elapsed from King’s departure, I became so uneasy at the delay that I decided to wait no longer. I was aware that our troops had been engaged in hostilities with the Spanish Utahs and Apaches…and became fearful that they (King’s party) has been cut off by these Indians “…my intention was to make the Red River settlement about twenty-five miles north of Taos, and send back the speediest relief possible” (120).

Fremont’s group met a party of Indians, said to be led by Chief San Juan—“an Utah, son of a Grand River chief we had formerly known” who gave the men four horses and promised to lead them to the Rio Colorado settlement. “By a present of a rifle, my two blankets, and other promised rewards when we should get in, I prevailed upon this Indian to go with us as a guide to the Red River settlement, and take with him four of his horses, principally to carry our little baggage.” (121). Fremont then caught up with the original party, now reduced to three men, who had been traveling for 22 days. Fremont reached Rio Colorado on Saturday, January 20th (122).

Fremont and another man went on to Arroyo Hondo and Taos to get more mules—there were only a few in Rio Colorado—and more provisions. Fremont later recounted that “The morning after reaching the Red River town, Godey and myself rode on to the Rio Hondo and Taos, in search of animals and supplies, and on the second evening after that on which we had reached Red River, Godey had returned to that place with about thirty animals, provisions, and four Mexicans, with which he set out for camp on the following morning. On the road he received eight or ten others, which were turned over to him by the orders of Major Beale [Beall], the commanding officer of this northern district of New Mexico” (123).

Fremont decided to stay with Kit Carson in Taos. On January 23rd, Godey, with people from Rio Colorado, including Jesus Valdez, and four muleteers from Arroyo Hondo, went back north to rescue the remaining parties. He reached the party with Richard Kern on January 28th, who described the rescue—“Godey came with Ferguson—almost missed us. F. returned to the other camp and brought us some bread and corn meal on the 29th—Also a Spaniard & horses & mules…” (124). Kern reached Rio Colorado on February 9th—“Moved on to Rio Colorado 15 miles—got there about sunset, and slept in a house—met Preuss and Creutzfeldt [two expedition members].”

Thomas Martin described reaching Rio Colorado—“When we arrived at the settlements, a small town on the Red river we found Williams and his party there. This town or Pueblo is about 30 miles N.W. of Taos, N.Mex. There we laid 10 days stopping at a Hotel kept by a Frenchman” (125). Micajah’s McGehee told of their rescue by Alexis Godey and people from Rio Colorado—“Relief it was, sure enough, for directly we spied Godey riding toward us, followed by a Mexican. We were all so snowblind that we took him to be the Colonel until he came up and some saluted him as the Colonel…Dismounting, he quickly distributed several loaves among us, with commendable forethought giving us but a small piece at first, and making us wait until the Spaniard could boil some for us, or prepare some ‘tole’ (boiled cornmeal), which he quickly made and this we quickly devoured.”

McGehee described the “little outer settlement of Rio Colorado” where “obtaining what provisions he could, and hiring several Spaniards with mules, Godey set out as speedily as possible up the river. On his way he fell in with two other Mexicans, who, with mules loaded with bread and flour and cornmeal, were going out to trade with the Utah Indians. These he pressed into service…” (127). One of the Rio Colordo members of the resuce teams, Jesus Valdez, later settled Del Norte in 1859.

Another account of reaching Rio Colorado was given by Thomas Breckinridge.—“For nearly the entire distance we crawled on ice or through snow…Our suffering was almost beyond description. Those who have been affected by snow-blindness can appreciate our situation. Our feet had been so frozen and thawed that the flesh began to come off….We finally reached the settlement [Rio Colorado], about ten o’clock at night. The people had been expecting us, as Fremont and his party had stopped there and informed them that we were on the way. The settlement was located in a small valley, and was called the ‘Red River Settlement.’ We were received very kindly by the Mexicans, who did everything to alleviate our distress. The Alcade’s wife, a Mexican woman, attended to our frozen limbs, bathing them several times a day with Juniper tea” (128).

By early February, all of the survivors also reached Rio Colorado. The surviving rescue party members reached Taos on February 12th, 1849. Fremont left that same day to pursue the lower Spanish Trail to California. Of the 32 men who had started out with Fremont, 21 survived the expedition. Fremont tallied up the damage of his failed expedition. “After a long delay…Mr. Haler came in last night [Feb 5th 1849], having the night before reached the Red River settlement, with some three or four others. Including Mr. King and Proue, we have lost eleven of our party” (129).

Fremont, in a letter to his wife, blamed it all on the guide Williams—“The error of our journey was committed in engaging this man. He proved never to have in the least known or entirely to have forgotten the whole region of country through which we were to pass. [Note that Fremont thought that Abiquiu was the closest settlement to their location in the La Garita Mountains.] We occupied more than half a month in making the journey of a few days, blundering a tortuous way through deep snow which already began to choke up the passes, for which we were obliged to waste time in searching” (130).

As leader of the expedition, Fremont was the responsible party, but it is clear that his court martial had changed him. “I say briefly, my dear Jessie, because now I am unwilling to force myself to dwell upon particulars. I wish for a time to shut out these things from my mind, to leave this country, and all thoughts and all things connected with recent events, which has been so signally disastrous as absolutely to astonish me with a persistance of misfortune, which no precaution has been adequate on my part to avert” (131).

E.M. Kern, a member of the expedition, writing to his wife Mary from Taos faced the issue more directly—“You will think it strange I have no doubt when you learn of our remaining here instead of going on with Fremont, but our tale is soon told that will give you an idea of the why and wherefore. In the first place he has broken faith with all of us.” He described Fremont as one “…who loves to be told of his greatness…” and “jealous of anyone who may know as much or more of any subject than himself…” Most interesting about this letter is a drawing, presumably by E.M. Kern, showing two expediton members watching over a dying member of their party.

Such was Rio Colorado’s experience with the “great” man. A detailed description of the expedition and the route that Fremont’s expedition followed can be found in Patricia Richmond’s book Trail to Disaster (132), as well as a discussion of the controversies involving Old Bill Williams possible sabotage of the expedition and the allegations of cannibalism. The route of Fremont’s expedition can also be explored using the directions in Richmond’s book and directions provided at a Web site (132). Fremont never wrote much about this expedition, and most of the details are found in the diaries of surviving expedition members, including the Kern brothers, Thomas Breckenridge, and Micajah McGehee. Notably, Richard H. Kern, the expedition artist, produced some of the first paintings of this area (133).

Notes

114. John Fremont, 1813-1890. www.johnfremont.com, accessed 11/9/02.

115 Favour, Alpheus H. Old Bill Williams, Mountain Man. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1936, pp 172-196. 115-117. Hafen, Le Roy R, and Hafen, Ann W. Fremont’s Fourth Expedition: A Documentary Account of the Disaster of 1848-1849. The Arthur H. Clarke Company, Glendale, CA 1946.

116. Favour, Alpheus H. Old Bill Williams, Mountain Man. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1936, pp 172-196.

118. Summary of John Charles Fremont’s Fourth Expedition, 1848-1849. www.slv.org/history- fremont.html, accessed 11/14/02.

119–131. Hafen, Le Roy R, and Hafen, Ann W. Fremont’s Fourth Expedition: A Documentary Account of the Disaster of 1848-1849. The Arthur H. Clarke Company, Glendale, CA 1946.

124. Weber, David J. Richard H. Kern: Expeditionary Artist in the Far Southwest, 1848-1853. Amon Carter Museum by the Museum of New Mexico Press, 1985.

130. Favour, Alpheus H. Old Bill Williams, Mountain Man. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1936, pp 172-196.

132. gorp.away.com/gorp/resource/us_national_forest/co/see_riog.htm, accesssed 11/14/02; Richmond, Patricia Joy. Trail to Disaster: The Route of John C. Fremont’s Fourth Expedition from Big Timbers, Colorado, through the San Luis Valley, to Taos, New Mexico. University Press of Colorado, Colorado Historical Society, Denver, CO, 1989, 1990

133. Weber, David J. Richard H. Kern: Expeditionary Artist in the Far Southwest, 1848-1853. Amon Carter Museum by the Museum of New Mexico Press, 1985.