Landscape is an important backdrop to the events of history—the stage upon which it occurs—and sometimes even an actor. This has certainly been true throughout the history of the Questa area.

—Judy Cuddihy

Driving north up Route 522 from Taos, up to the top of the Mile Hill, and then down from La Lama, the very southernmost part of the San Luis Valley appears and the village of Questa comes into view, much as the geological scene first appeared to settlers coming up from Taos in the early 19th century. A glance to the east and to the west gives hints of the tumultuous geological happenings in this area, for the Questa area was truly born in fire and ice.

Questa itself sits on the Questa Caldera, a collapsed volcano. The landscape that we face today is the result of a huge volcanic explosion, centered on what is now Latir Peak, that occurred here some 25 million years ago. This explosion was so powerful that molten rocks from the explosion were thrown as far south as Penasco as well as north beyond Costilla. The volcano collapsed, forming a caldera, and then the floor of the collapsed volcano, moved by tremendous geological forces, rose up again to form Pinabete, Venado, Carbresto, and Virsylvia Peaks.

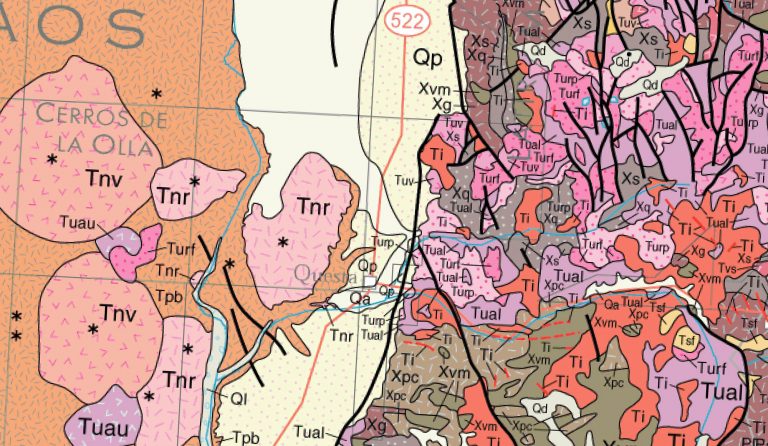

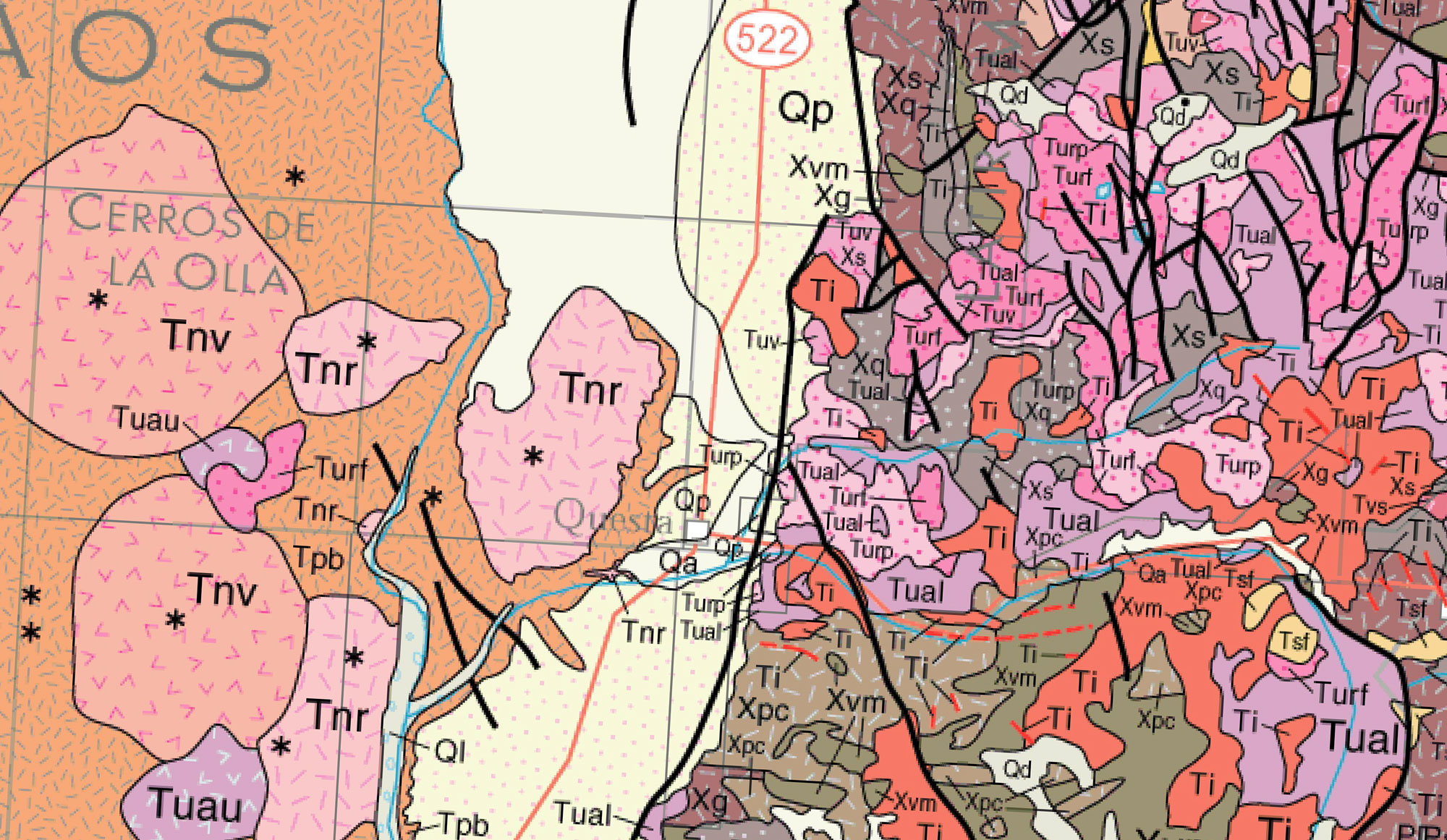

compiled by O.J. Anderson, G.E. Jones, and G.N. Green

USGS Open-File Report OF-97-52

Digital data base by G.N. Green and G.E. Jones

New Mexico Bureau of Mines and Mineral Resources

U.S. Geological Survey, Department of the Interior 1997

Flag Mountain is the the southernmost wall of this volcano; other boundaries have been found along Mallette Canyon (eastern boundary), Bonito Canyon (eastern margin), and further north to the north side of Jaracito Canyon (at Virsylvia Peak). Goat Hill is formed of volcanic rock from the Questa Caldera. The Mallette Canyon Road from Questa to Red River travels right through the the caldera, and the Latir Wilderness area is the core of the Caldera. Today’s Route 38 more or less follows the southern boundary of the Questa Caldera. Volcanic rock from this explosion, called Amalia Tuff, can be seen in the Costilla Valley and it forms the ridge between Cabresto Creek and the Red River. Elephant Rock is actually a large block of quartz and latite that slid down from the southern wall of the Questa Caldera.

The Rio Grande Rift of the Taos Plateau, just west of Questa, is a divergence in the North American tectonic plate that reaches down 36,000 feet into the earth (below the Rio Grande Gorge), and was formed about 36 to 25 million years ago (some sources give 18 million years ago). This tremendous down-fault is filled with alluvial silt, or sand and soil washed down from the mountains over the millenia. In our area, this fill is about 30,000 feet deep; without this alluvial fill, the Rio Grande Rift would be an open canyon six times deeper than the Grand Canyon. This Rift is still widening in New Mexico. The volcanic peaks on the Taos Plateau became active around 10 million years ago and erupted periodically up to about 2 million years ago.

Other significant geological events occurred in this area. Even earlier than these explosive events, about 300 million years ago, this entire area was part of a huge inland sea. The Sangre de Cristo Mountains rose up from the bed of this inland sea about 286 million years ago. Water returned to this area again about 1.6 million years ago in successive waves of moving ice during the march of huge glaciers over North America. These glaciers covered much of the Sangre de Cristo Mountains. The Moreno Valley is the most obvious evidence of their passage, as are the glacially created lakes on Latir Peak and the glaciers on Blanca Peak, which are the southernmost glaciers in the United States (1).

The result of much of this activity is a rich supply of minerals in the area, including molybdenum porphyry, iron hydroxides, iron sulfates, clays, micas carbonates, quartz, kaolinite, and gypsum (2).

With all of this geologic history on a grand scale, the history of humans in the area is very recent historically speaking. And it is with that history that we begin our story.

Notes

1. Bauer, D.W., Love, J.C., Schilling, J.H., and Taggart, J.E., Jr. The Enchanted Circle—Loop Drives from Taos. NM Bureau of Mines & Mineral Research, Socorro, NM, 1991; Chapin, C.E. The Rio Grande Rift, Part I: Modifications and Additions, pp. 191-201. In James., H.L. (ed). Guidebook to the San Luis Basin, Colorado. NM Geological Society, 1971; Chapin, C.E., and Zidek, J. (eds) Field Excursions to Volcanic Terranes in the Western United States. Vol I: Southern Rocky Mountain Region, Memoir 46. NM Bureau of Mines & Mineral Research, 1989; James, Guidebook of the San Luis Basin, 1971; Peterson, R.C. Glaciation in the Sangre de Cristo Range, Colorado, pp. 165-167. In James., H.L. (ed). Guidebook to the San Luis Basin, Colorado. NM Geological Society, 1971.

2. U.S. Department of the Interior, U.S. Geological Survey, Mapped Minerals at Questa NM, Using Airborne Visible-Infrared Spectrometer (AVIRIS) Data. Preliminary Report, Open file report 02-0022, 2002.