A second group of settlers petitioned for a land grant on the Rio Colorado early in 1841, essentially for land that is now Questa proper. This petition was returned to the settlers by the Governor Manuel Armijo in a decree dated September 6th, 1841. “By order of his Excellency let the application of the petitioners be returned to them, as that which they request is inadmissible according to the report of the justice of their jurisdiction. And by superior order I sign it. Jorge Ramirez.”

Apparently permission had originally been granted by J. Andres Archuleta, Rio Arriba, Prefecture of the First District for a “possession on the Rio Colorado, in the vicinity of Taos, to sixty individuals who solicited it, and who are in possession, but there now appears of decree of the Most Excellent Governor, dated September 6 last past, which is literally September 6, 1841.”

On January 8th , Rafael Archuleta, Antonio Elias Armenta, and Miguel Montoya and 35 families filed a petition with Don Juan Andres Archuleta, Prefect of the First District of the Deparment of New Mexico for a tract of land on the Rio Colorado (80). These pobladores, or settlers, stated in their January 8th petition that “..finding ourselves in want of land for the support of our families, and believing that the public lands should be given to those, who take an interest in developing them for the promotion of agriculture…” they should be granted “…the land which we solicit at El Rio Colorado..” which is “…very fertile for the purpose which we solicit it…” (81).

In the January 19, 1842 Posecion document by Don Juan Antonio Martin, Justice of the Peace for the First and Second jurisdictions, a tract of land was approved. Martin, describes that “…I, said Justice of the Peace in the company of two witnesses, the citizens Juan Andres Lovato and Jose Antonio Gutierres, finding the mentioned land free and public there being present 35 families, I made them understand and know the petition they had made and the superior decree and expressed to them that for the purpose of possession, they had to observe and comply with the following conditions.”

This is followed by another document dated February 22, 1842, from Archuleta asking for the matter to be brought before the Governor “…in order that His Excellency may state whether the possession already given shall be carried into effect or be revoked….”

A reply from the “The Secretary of the Government, Don Guadalupe Miranda” to Archuleta on February 24th states that (79):

Having reported to His Excellency the governor with your note of 22nd inst. he has has instructed me to inform you that that granting or refusing of those lands for colonization is peculiar to the Departmental Assembly but in order that your action many not be without effect he directs that the parties in possession may thus remain, and subject to the action that may be taken by said Excellent Assembly when it convenes, which will call before it the reports of the proper authorities.

On the other hand the fact of this government having refused permission to those who asked it led also to the observation that for the present it is not proper that the population be scattered and particularly at such a distance from the frontiers, on account of the risk to which they are exposed from the enemies of the union—the Texans; and that being so far away they cannot protect themselves, and they furnish the enemy a base for operations and supplies, which causes incalculable damage to the Department.”

This reasoning is surprising, given the long-standing policy of having armed settlers defend the frontier against the marauding Indians from the north and east and the Americans and the French.

As was required by law, the petitioners came and threw a piece of sod to indicate possession of the land. Martin said that after hearing the conditions, the settlers “responded in a unanimous voice that the orders will be remembered and understood.” He then said,“I conducted them over said land, they pulled out grass, and shouted with joy ‘Long live the sovereign powers of the Mexican nation and the constituted authority’…” (82).

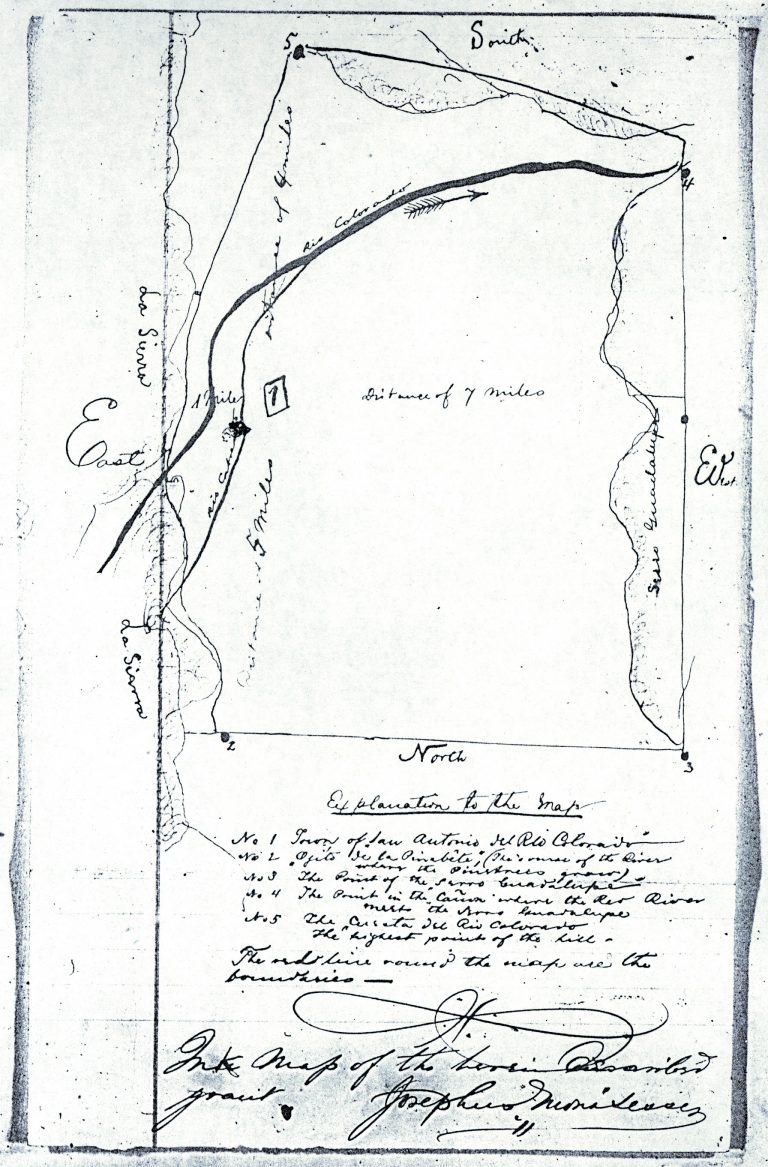

The boundaries of the grant were described as: “Por el Norte el ojito de los pinabetes y la punta del cerro de guadalupe pro el sur cuesta oseja del rio colorado por el oriente la ciendra y por el poniente el dicho cerros de guadalupe con el rio colorado” (To the north the source of the river of the pine trees (ojito de la Pinabete) and the point of the Cerro Guadalupe. To the south the cuesta del Rio Colorado, to the east the Sierra, and to the west the Canon where the above-mentioned Serro de Guadalupe joins with the Rio Colorado in which circuit is contained the given land.) (see Figure 21) (83).

The original Posecion document (84) (see Figures 15–20) also described a “…surplus on the upper side, at the rito del cabresto, without being distributed and the meadow in front of the plaza which remains for the benefit of all in common, that is to say it cannot be cultivated, and below there remained another surplus without being distributed up to the mouth—puesta— of the canonsito, there also remains within the possession the island lying between the two Rivers, that being the place where the citizen Antonio Elias Armenta, settled and his son-in-law, Francisco LaForee [Laforet] to whom were designated a greater number of varas of land than to those to whom corresponded in a direct line on account that said island is of small extent and this Senor Armenta being ascending to the right of priority in the petition they made, there were also entitled to the right of priority, Rafael Archuleta and Miguel Montoya, who made every effort to obtain the possession advising the colonists that the pastures and watering places are common as remains stated, and the for entrance and exits to the towns shall remain ample and free where it may be deed proper, also said plazas shall have drainage on the North side to the sejita—little brow— near the woods, and in the south to the little river at the foot of the sejita where the water is taken out for the plaza, on the east forty varas for drainage and easements and on the west 40 varas more for the same purpose aforesaid.” The total acreage in the grant was approximately 110,000 acres.

All of these requirements are characteristic of the villages established in the the upper Rio Grande valley—a community pasture, la vega; a community upland pasture, or ejido; long-lot fields, or extensions, parallel strips of land running at right angles to streams or acequias; and fortified pastures (85).

Thus, the pobladores of Rio Colorado became landed neighbors, or vecinos. They were the beneficiaries of a decree issued in 1812 by Charles IV of Spain, which ordered the officials in New Spain to distribute vacant royal lands to “loyalist defenders” and thus create a new class of small landholders (86). From about 1591 until this time, the Spanish monarchy had protected Indian lands and ordered that their communal lands should not be invaded nor should their villages be subject to the process of composicion.

By taking the name of St. Antonio to designate their village, the settlers were mirroring their religious and social values (87), the all-important adhesive that would hold together their settlement under difficult conditions. Because there were no priests and the “law,” such as it was, was in Taos, these early settlers used their religious customs to enforce the moral order of the community.

Affixed to the petition for the grant were names from 35 families, as required by the colonization laws of 1824 and 1829. (The names attached are listed in the Appendix.) It is interesting to note that one of the names listed is that of one Carlos Hortives for 100 varas. This was one of the many spellings of the name Charles Autobees, of whom there will be more in subsequent pages.

To keep this land, the settlers had to agree to live on the land and maintain the common lands, to possess weapons to defend the land, to cultivate the land for 4 years before being able to sell it, and to fortify the town. The fortified plaza would have been built on high ground of mud-plastered logs (jacals or xacales placed side by side vertically in a trench). Once these temporary buildings were constructed, many layers of mud plaster were added, horizontal bond beams stabilized the vertical logs, and vigas and latillas were added to make a roof. Houses of the plaza were built side by side and each house had “single-file” rooms with no windows and doors opening onto the interior courtyard. The courtyard was closed off by a fortified wooden gate. The only extant building of this nature in the area, and prob ably much grander than any fortified plaza in Rio Colorado, is the Martinez Hacienda in Taos. Dispensas, or outbuildings, were located outside the plaza. These fortifications were very much needed because of the frequent Indian depredations on this tiny village by the Utes from the north and by the Apaches. These raids would continue on and off in Rio Colorado throughout much of the 19th century.

These fortified plazas evolved into plazuelas—Lor U-shaped buildings or family compounds— once the threat of Indian attacks subsided. Questa examples are the Rael and Gallegos plazuelas. Once farming was underway and the community was more established, square or rectangular buildings of one or two rooms were constructed of adobe and had flat roofs.

The Justice of the Peace was called back to Rio Colorado many times to settle questions and disputes regarding the land. On May 14, 1843, Jose Miguel Sanchez designated land to new colonists in Rio Colorado. He noted that “…this instrument remains and will remain attached to the royal possession which rests in the person of Don Antonio Elias Armenta….” (88). Dioniso Gonzales, Justice of the Peace of Arroyo Hondo, was asked to come to Rio Colorado on July 13, 1844 to reconfirm boundaries of “lands of the Rio Colorado….And having in my hands the royal grant and donation I commenced to examine the lands….I raised the line and commenced to measure the lands of the citiziens Antonio Elias Armenta and his son-in-law Francisco Lafore and Francisco Armenta….” Apparently there was a dispute between Armenta and Juan Benito Valdez regarding their land, as the Justice of the Peace mentions a lawsuit—“…it is not stated in the note where two hundred varas of land were given to said Juan Benito and not stated in the donation that said Valdez has the stated varas on a straight line from here to Rio del Cabresto.” (89). The Justice of the Peace is back in Rio Colorado on July 24, 1844 regarding the dispute between Armenta and Valdez. He reaffirms the boundaries but both parties refuse to sign the document.

On November 11, 1845, Justice of Peace Dionisio Gonzales declared the San Antonio del Rio Colorado grant “legal and valid in all its parts and purposes as intended by the grantors.”

In 1847, Justice of Peace Lorenzo Martin came up to Rio Colorado to settle the issue of roads on the land grant. He set out 100 varas as an outlet of the plaza and 50 varas for common entrances and outlets. “I fixed their respective boundaries, so that at no time will they have any dispute nor pretext of ignorance, leaving on the partition of lots on the upper side of the plaza (town) already built, fixing as the boundaries of the town, on the east, la Cuchillita (small ridge) leaving as a road room enough for one wagon; on the north in case no other town is built, and if the families of the same, who possess the land may encrease [sic], they may enjoy as drainage what is designated on the grant; on the south, following the former town, and on the west, the forty which have the original town….” This document also designates Don Francisco Lafore as Senor Alguacil (Sheriff ).

While the Rio Colorado settlers were establishing their houses and farms, the traffic of traders and now the U.S. Army also continued through Rio Colorado. Letters and notes regarding Bent’s Fort to the north tell of large sums of money carried along the trail from Santa Fe to Bent’s Fort—for example $28,000 in specie carried by a party including William Bent, Simpson and others in April of 1844 (90). They too were experiencing problems with the Indians. As described in the St. Louis Reveille in 1844, “Several different tribes, the Chayennes, Sioux, Apaches, Kiawas, and others, as is supposed, were scouring the plains ‘in cahoot,’ but for the prompt action of the traders in drawing themselves up and forming their defence, there is little doubt that they would have been stripped of their property and, perhaps slaughtered.” Regarding the Comanches, “They are daring and desperate Indians when once embarked in an enterprise, but they seldom attack until they see advantage clearly on their own side” (90).

By the mid-1840s the northern frontier was dependent on this traffic of American traders for merchandise and for markets to sell their goods. Trade with Chihuahua was both time-consuming and expensive, and thus imports from the East began to grow. Imports from America to Santa Fe were estimated to be $145,000 per year during this period (91). Settlers in the northern part of the New Mexican territory began to fear that Mexico might try to sell New Mexico to the United States. New Mexicans said they would rather be an independent state “Republica Mexicana del Norte” than suffer this fate.

At about this time the Navajos joined forces with the Utes to attack the frontier settlements of northern New Mexico, portending an even more miserable state of affairs for the settlers in Rio Colorado. George Simpson, on a trip south to Taos with his wife for the baptism of their child in 1844, reports an encounter with the Utes north of Rio Colorado. When they arrived in Rio Colorado, Simpson found that the Utes had killed several herders and three people traveling to Taos (91a).

A letter of September 20, 1844 from one “J.B.” at Fort William on the Arkansas River describes a letter (92) from George Bent in Taos of September 9th reporting a Mexican and Indian War between

“…a portion of the Eutaw Indians and the citizens of New Mexico. It appears that sometime last fall, the former Governor of Santa Fe (Armijo) granted to a Frenchman, named Portalance, and an Englishman, by the name of Montgomerie, authority to raise a party for the purpose of invading the territory of the Navajo Indians, with whom the Mexicans were then at war, but returning from the Navajos, rather unsuccessful, they fell in with a band of Eutaws, who were then at peace with the Mexicans, killled several of them, and drove off a number of their horses and mules.

“A few days previous to the date of Mr. B’s letter, the Eutaw Chief (Spanish Cigar) called upon the present Governor (Martines) at Santa Fe and demanded satisfaction for the outrage committed on this tribe. The Governor refused to give him the desired satisfaction, and the Indian seized him by the throat, and commenced shaking him. Martines drew his sword, and run the Indian through his body; –he then gave orders to his soldiers to fire, and six of the Indians who had accompanied the Eutaw Chief were killed upon the spot.”

This killing of the Ute Chief , whose real name was Panasiyave, was bad news for Rio Colorado. In revenge, the Utes attacked Rio Colorado in October of 1844 along with other villages north of Santa Fe and then early in 1845, they attacked Rio Colorado again along with Ojo Caliente and the Pueblo of Taos. Sixty armed Mexicans were sent out of Taos to go after the Utes, but they had no luck. It was not very helpful to learn that Americans at Pueblo and Hardscrabble were supplying the Indians with guns and ammunition in return for the horses and mules stolen from the settlers at Rio Colorado and other northern village. Another early settler at Rio Colorado, Marcelino Baca, was also an early settler of Greenhorn and Pueblo in Colorado. Indian attacks on these early settlements resulted in Baca losing 117 fanegas of corn to the Utes in one raid, driving him back to the relative safety of Rio Colorado (93).

A letter of July 27th, 1845 published in the St. Louis Reveille on September 16th, 1845, describes the northern New Mexicans as

“…still amicably disposed to our people [i.e., the traders and trappers]. Whether there is really a declaration of war on the part of the Mexicans, these northern people are equally in the dark with ourselves. I do not anticipate any trouble with them in any event.”

An eastern traveler, A. Wizlizenus, with Col Doniphan’s expedition in 1846 and 1847, describes a meeting with frontier settlement Mexicans, possibly even from Rio Colorado, out on a buffalo hunt somewhere near the Cimarron River (94).

“While we were travelling to-day over the lonesome plain, men and animals quite tired and exhausted, on the rising of the hill before us quite suddenly appeared a number of savage looking riders on horseback, which at first sight we took for Indians; but their covered heads convinced us soon of our mistake, because Indians never wear hats of any kind; it was a band of Ciboleros, or Mexican buffalo hunters, dressed in leather or blankets, armed with bows and arrows and a lance—sometimes, too, with a gun—and leading along a large train of jaded pack animals. Those Ciboleros are generally poor Mexicans from the frontier settlements of New Mexico, and by their yearly expeditions into the buffalo regions they provide themselves with dried buffalo meat for their own support and for sale….They are never hostile towards white men, and seem to be afraid of the Indians. In their

manners, dress, weapons, and faces, they resemble the Indians so much, that they may be easily mistaken for them.”

A Spaniard’s description of Rio Colorado in 1845 is provided by Pablo Dominguez in testimony for a Surveyor General’s Office case (95). He had been in the military when he visited Rio Colorado in September 1845.

“The place is on the main road running northward from the town of Taos and about 15 or twenty miles from Taos. When I was at the place there were residing there about 45 or 50 families. When I was there I was in command as lieutenant of a detachment of soldiers sent by the military commander Archuleta in pursuit of some Panano (Cheyenne) Indians who had been killing some shepherds in that section of country. According to my recollection, the town was built of adobe and lumber principally of the latter. The most of the adobe buildings contained upon them loopholed battlements placed there for defence in fighting off the hostile Indians. There were fields there planted with corn and beans, and in the vicinity I saw pasturing in charge of herders considerable numbers of cattle. My orders were to scour the country throughout that section for Indians….”

With George Frederick Ruxton’s arrival in Rio Colorado in the 1840s, we get the first really detailed description of life in Rio Colorado in the mid-1840s (96). Ruxton, one of the first Anglo tourists to reach this area, was traveling north from Taos to the settlement at Rio Colorado. His colorful description, complete with the prejudices of the time held by many of the Anglos from the East, provides a wide-ranging view of what life was like for the vecinos of Rio Colorado. These extended excerpts are included because of the detail they provide about life in Rio Colorado in the mid-1840s.

“All this day I marched on foot through the snow, as Panchito made sad work of ascending and descending the mountain, and it was several hours after sunset when I arrived at Rio Colorado, with one of my feet badly frozen. In the settlement, which boasted about twenty houses, on inquiry as to where I could procure a corral and hoja for the animals, I was directed to the house of a French Canadian-an old trapper named Laforey [Laforet]-one of the many who are found in these remote settlements, with Mexican wives, and passing the close of their adventurous lives in what to them is a state of ease and plenty; that is, they grow sufficient maize to support them, their faithful and well-tried rifles furnishing them with meat in abundance, to be had in all the mountains for the labor of hunting.

I was obliged to remain here two days, for my foot was so badly frozen that I was quite unable to put it to the ground. In this place I found that the Americans were in bad odor; I came in for a tolerable share of abuse whenever I limped through the village.”

Of the village itself, Ruxton wrote:

“Rio Colorado is the last and most northern settlement of Mexico, and is distant from Vera Cruz 2000 miles. It contains perhaps fifteen families, or a population of fifty souls, including one or two Yuta Indians, by sufferance of whom the New Mexicans have settled this valley, thus ensuring to the politic savages a supply of corn or cattle without the necessity of undertaking a raid on Taos or Santa Fe whenever they require a remount. This was the reason given me by a Yuta for allowing the encroachment on their territory.

The soil of the valley is fertile, the little strip of land which comprises it yielding grain in abundance, and being easily irrigated from the stream, the banks of which are low. The plain abounds with alegria, the plant from which the juice is extracted with which the belles of Nuevo Mejico, cosmetically preserve their complexions. The neighboring mountains afford plenty of large game-deer, bears, mountain-sheep, and elk; and the plains are covered with countless herds of antelope, which, in the winter, hang about the foot of the sierras, which shield them from the icy winds.

No state of society can be more wretched or degrading than the social and moral condition of the inhabitants of New Mexico: but in this remote settlement, anything I had formerly imagined to be the ne plus ultra of misery, fell far short of the reality —such is the degradation of the people of the Rio Colorado. Growing a bare sufficiency for their own support, they hold the little land they cultivate, and their wretched hovels on sufferance from the barbarous Yutas, who actually tolerate their presence in their country for the sole purpose of having at their command a stock of grain and a herd of mules and horses, which they make no scruple of helping themselves to, whenever they require a remount or a supply of farinaceous food. Moreover, when a war expedition against a hostile tribe has failed, and no scalps have been secured to ensure the returning warriors a welcome to their village, the Rio Colorado is a kind of game-preserve, where the Yutas have a certainty of filling their bag if their other covers draw blank. Here they can always depend upon procuring a few brace of Mexican, scalps, when such trophies are required for a war-dance or other festivity, without danger to themselves, and merely for the trouble of fetching them.

Thus, half the year, the settlers fear to leave their houses, and their corn and grain often remain uncut, the Indians being near: thus the valiant Mexicans refuse to leave the shelter of their burrows even to secure their only food. At these times their sufferings are extreme, they being reduced to the verge of starvation; and the old Canadian hunter told me that he and his son entirely supported the people on several occasions by the produce of their rifles, while the maize was lying rotting in the fields. There are sufficient men in the settlement to exterminate the Yutas, were they not entirely devoid of courage; but, as it is, they allow themselves to be bullied and ill-treated with the most perfect impunity.”

Ruxton describes life in Rio Colorado and Laforet’s unique personlity:

“The fare in Laforey’s house was what might be expected in a hunter’s establishment: venison, antelope, and the meat of the carnero cimarron the Rocky Mountain sheep furnished his larder; and such meat (poor and tough at this season of the year), with cakes of Indian meal, either tortillas or gorditas, (The tortilla is a round flat pancake, made of the Indian cornmeal; the gordita is of the same material, but thicker) furnished the daily bill of fare. The absence of coffee he made the theme of regret at every meal, bewailing his misfortune in not having at that particular moment a supply of this article, which he never before was without, and which I may here observe, amongst the hunters and trappers, when in camp or rendevous, is considered as an indispensable necessary. Coffee, being very cheap in the States, is the universal beverage of the western people, and finds its way to the mountains in the packs of the Indian traders, who retail it to the mountain-men at the moderate price of from two to six dollars the half-pint cup. However, my friend Laforey was never known to possess any, and his lamentations were only intended to soften my heart, as he thought (erroneously) that I must certainly carry a supply with me.

“Sacre enfant de Garce,” he would exclaim, mixing English, French, and Spanish into a puchero-like jumble, “voyez-vous dat I vas nevare tan pauvre as dis time; mais before I vas siempre avec plenty cafe, plenty sucre; mais now, God dam, I not go a Santa Fe God dam, and mountain-men dey come aqui from autre cote, drink all my cafe. Sacre enfant de Garce, nevare I vas tan pauvre as dis time, God dam. I not care comer meat, ni frijole, ni corn, mais widout cafe I no live. I hunt may be two, three day, may be one week, mais I eat notin’; mais sin cafe, enfant de Garce, I no live, parce-que me not sacre Espagnol, mais one Frenchman.”

After three days of hospitality and abuse in Rio Colorado, Ruxton left for the Arkansas River:

“Laforey escorted me out of the settlement to point out the trail (for roads now had long ceased), and bewailing his hard fate in not having “plenty cafe, avec Sucre, God dam,” with a concluding enfant de Garce, he bid me good bye, and recommended me to mind my hair in other words, look out for my scalp. Cresting a bluff which rose from the valley, I turned in my saddle, took a last look of the adobes, and, without one regret, cried “Adios, Mejico!”

I had now turned my back on the last settlement, and felt a thrill of pleasure as I looked at the wild expanse of snow which lay before me, and the towering mountains which frowned on all sides, and knew that now I had seen the last (for some time at least) of civilized man under the garb of a Mexican sarape.”

But this influx of Americans was proving troublesome and upsetting the balance between the Indians and Mexico. In 1843, Padre Antonio Jose Martinez told the Mexican President that Americans were now providing firearms to the Indians. The Indians used these firearms to raid the settlers’ cattle and livestock and then traded the spoils back to the Americans for more firearms and other goods. Thus, the Americans were providing a new market for the stolen property and as Padre Martinez put it contributing “..to the moral decay of Indians and of encouraging Indian depredation on New Mexico” (97). But the American onslaught was not to be held off and the settlers in Rio Colorado were about to encounter a new government.

Notes

79. San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 33:521 case 4, Private Land Claims Court. NM State Records Center and Achives, Santa Fe.

80. San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 33:521 case 4, Private Land Claims Court. NM State Records Center and Achives, Santa Fe.

81–84. San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 20:1223 SG 76, Surveyor General’s Office. NM State Records Center and Achives, Santa Fe.

85. The Culebra River Villages of Costilla County, Colorado. National Register of Historic Plac- es. Multiple Property Submission. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Valdez and Associates, 2000 and Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Denver, Colorado.

86. Greenleaf, Richard E. Land and water in Mexico and New Mexico, 1700-1821. New Mexico Historical Review. XLVII:82-112.

87. The Culebra River Villages of Costilla County, Colorado. National Register of Historic Places. Multiple Property Submission. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Valdez and Associates, 2000 and Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Denver, Colorado.

88. San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 33:521 case 4, Private Land Claims Court. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe.

89. San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 33:521 case 4, Private Land Claims Court. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe.

90. Letters and notes from or about Bent’s Fort, 1844-1845. The Colorado Magazine XI, 223-227, 1934.

91. Lecompte, Janet. Pueblo, Hardscrabble, Greenhorn: The upper Arkansas, 1832-56. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1978; Weber, David J. The Mexican Frontier, 1821–1846: The American Southwest under Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1982.

92a. Letters and notes from or about Bent’s Fort, 1844-1845. The Colorado Magazine XI, 223- 227, 1934.

93. Lecompte, Janet. Pueblo, Hardscrabble, Greenhorn: The Upper Arkansas, 1832-56. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1978, pp. 162–163, 252.

94. Wislizenus, A. Memoir of a Tour to Northern New Mexico Connected with Col. Doniphan’s Expedition, 30th Congress, 1st session, misc. no. 26, 1848. The Rio Grande Press Inc, Glorieta, NM. 94. Wislizenus, F.A. Memoir of a tour to northern Mexico, connected with Colonel Doniphan’s Expedition in 1846 and 1847. Calvin Horn Publisher, Albuquerque, 1969.

95. Canon del Rio Colorado land grant, SANMI roll 22:447 SG 93, Surveyor General’s Office. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe.

96. Ruxton, George F. Wild Life in the Rockies. The MacMillan Company, New York, 1916.

97. Weber, David J. Myth and History of the Hispanic Southwest. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1988.