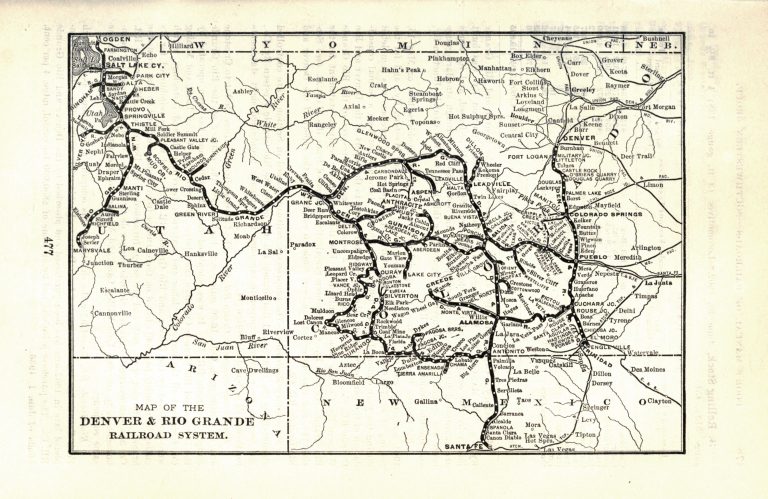

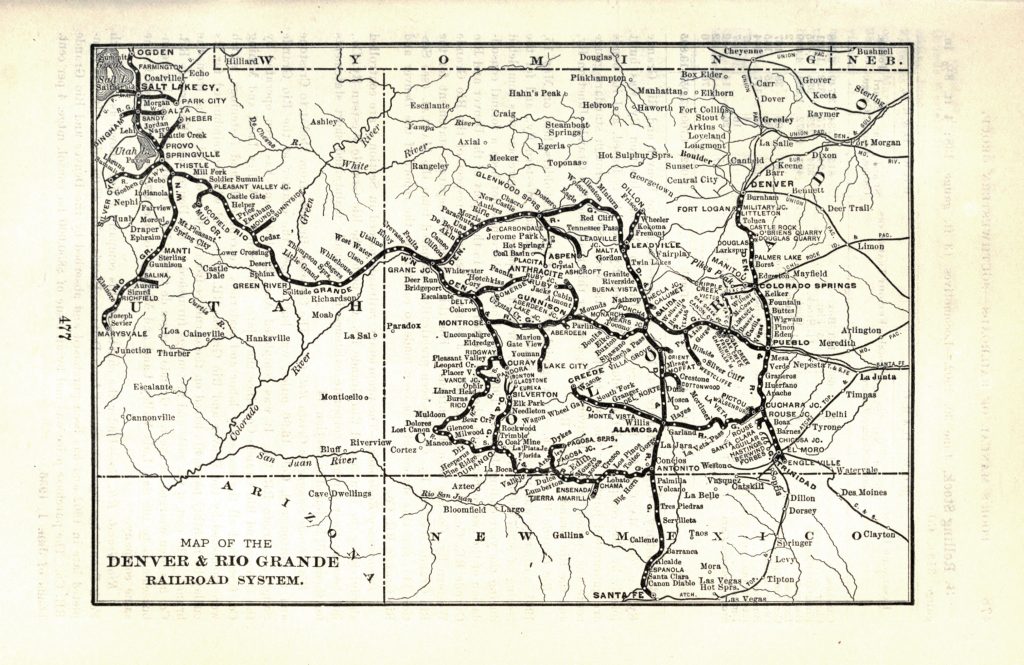

The 1870s brought more surveyors for the railroad that would come eventually through just north of Rio Colorado. By 1876, rail for the narrow-gauge Denver & Rio Grande Railroad was approaching Cucharas to the north and La Veta. The next year it had extended to the Fort Garland area and a new town, Garland City, sprang up almost overnight. The route of this railroad had been the Sangre de Cristo Trail, until the road turned south through Rio Colorado to Taos.

The railroad reached Alamosa in 1878, Antonito, Tres Piedras and Chamita, NM, and Cumbres Pass and Chama NM in 1880. The narrow-gauge track was replaced with broad-gauge track to Alamosa in 1898 (1). The southern terminus of the railroad, orginally to be El Paso, was instead Española. A southern spur went south from Antonito to Tres Piedras, and then south of Embudo it followed the river, and eventually ended at Santa Fe.

This train line, dubbed the Chile Line, ran three times per week between Antonito and Española. The total time from Denver to Espanola was 21 hours (2). Passengers could ride in open platform cars, the caboose, or the baggage car. One car per day carried lumber and livestock as well as hogs and wheat.

The stop nearest Rio Colorado was at Jaroso, where wool and cattle from Rio Colorado were shipped out for sale. In 1914, the Madera branch opened; it went from Taos Junction by way of Ojo Caliente to the Hallack and Howard Lumber Company in the mill town of Madera, and also ran to Embudo. People from northern New Mexico finally had a reasonably efficient way to send goods and produce out for sale. And adventurous tourists now had the means to visit the Pueblos that were near the Chile Line route. Vestiges of this line can still be found along current Route 285.

What the railroad introduced to areas in its path was a new cash economy; manufactured goods meant a diminution of the barter economy that had existed for centuries in this area. Many landholders could not afford to keep their property and had to look for employment. Agriculture and livestock production were commercialized and meadowlands became overgrazed. Many farmers fell into debt and were forced to sell their land and their water rights.

Notes

- Colvile, Ruth Marie. The Sangre de Cristo Trail. The San Luis Valley Historian, vol III, no. 1, 1971, pp. 11-33.

- Carl Heflin Collection, The Chile Line, The San Luis Valley Historian X, 7-10, 1978.