For almost a century, settlers in Rio Colorado had been subjected to the raids of Indian tribes. By the end of the 1870s, these raids were pretty much over. And throughout this long period there had been some cooperation with local Indians, particularly the Utes who had a camp just north of Rio Colorado and were said to have a camp where El Pueblito is now located. In addition to trading with these tribes, many locals went buffalo trading with the Comanches.

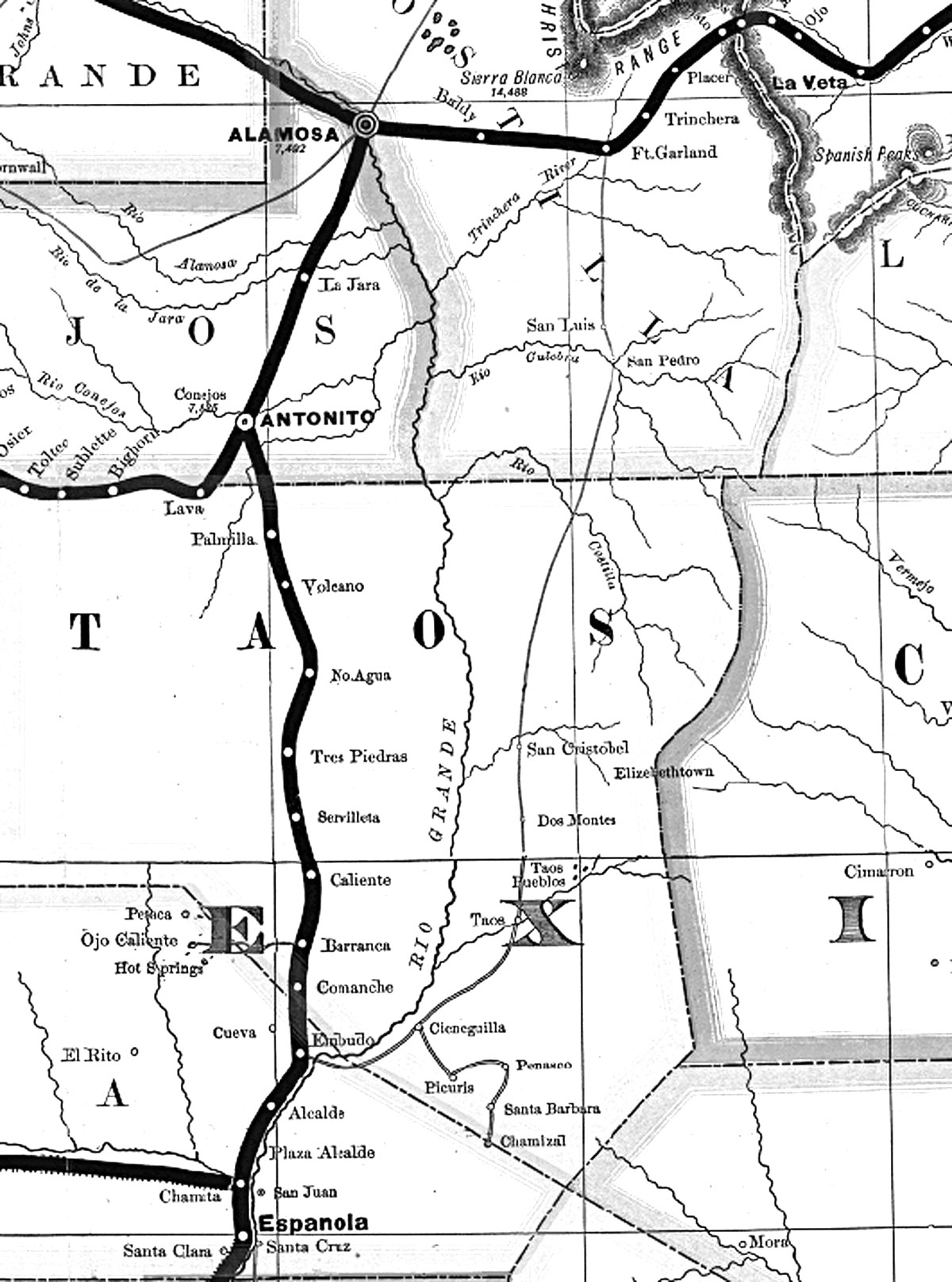

(Library of Congress)

One Vicente Romero of Cordova, interviewed by Lester (175), provides a vivid description of such a meeting. Supplied with “salt, blankets, and strips of iron for arrow-heads” and “big packs of a very hard bread, which our wives baked especially for trading to the Indians,” they set off via Mora past Fort Union to Indian country.

After signaling to the Indians with smoke, the Indians came and made camp near theirs. “After a sort of feast with the Indians we started in to trade. This would take a long time because there would be much talk over each trade.” Then they would engage in horse races and gambling and contests with bow and arrow as well as wrestling matches. They would also follow the buffalo herds. These were dangerous trips and any argument could quickly turn to ugly death. When they returned home, “We could see people on the roof-tops counting us as we rode down into the village to see who was missing. ..The next few days were filled with feasting and the nights with dancing.”

The Indian Wars in the West continued until about 1890. Once the Civil War ended, the floodgates opened with people coming West to seek gold, land, trade, and adventure, having a great impact on the Indians’ way of life, most notably with the hunting of buffalo, a mainstay of western and plains Indian life. The Army strategy was to establish a system of forts to protect the main travel routes and white settlements. Supplementing this approach were military operations against specific areas of Indian resistance using volunteer forces; in this area, these operations were conducted against the Utes and Apaches, Following the defeat of Indian tribes, government policy was to move the tribes to reservations. Some of the tribes kept to the reservation in the winter months, eating government rations, but when the warm weather made its appearance, they returned to the warpath. The Apache campaigns in the West did not end until the 1886 surrender of Geronimo. The last of the Indians wars were the legendary Custer’s Last Stand at Little Bighorn in June of 1876 and the battle of Wounded Knee in December of 1890.

There is little evidence of everyday life in Rio Colorado in the written record beyond the descriptions of visitors or the reminiscences of residents such as William Kronig. There do not seem to be any historical records of St. Anthony’s Church in Rio Colorado. Records of births, marriages, and deaths in the settlement were kept at the mission of San Geronimo at Taos (176) until 1865; then Sacred Heart in Costilla kept these records because there was no priest at Rio Colorado. The first marriage for Rio Coloradans recorded in Costilla was that of Jose Cisneros Cruz and Ramona Duran on May 20, 1865. The first burial was F.O. Jesus Garcia on May 29th, 1865. The Questa parish did not have its own priest until 1941 (see below).

Notes

175. Brown, L.B. “Los Comanches.” WPA New Mexico Writers’ Project, April 1937;

176. LDS Archives of Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Costilla—Sacred Heart, Burials 1865-1955, Box #59 LDS; LDS Archives of Archdiocese of Santa Fe, Costilla—Sacred Heart, Marriages 1865-1937, Box #59 LDS; M. Ochoa, Archives of the Archdiocese of Santa Fe, personal communication.