Our story now becomes less detailed. The end of the Indian raids and of the gold rush changed life in Questa to a more cyclical everday existence of farming, livestock raising, work at the moly mine, churchgoing—the cycle of birth, life, and death. Much of this life is within memories of the older residents of Questa and details of life in Questa during the early to mid-twentieth century are provided by Tessie Ortega in the following sections. There are a few items of note to be covered from the written record though.

The first of these concerns action taken against the discrimination suffered by Hispanics that was evident in many of the early descriptions of Rio Colorado by non-Hispanic travelers visiting the area. The influx of new people in search of gold and silver or coming in on the Denver & Rio Grande Railroad underscored this problem even more.

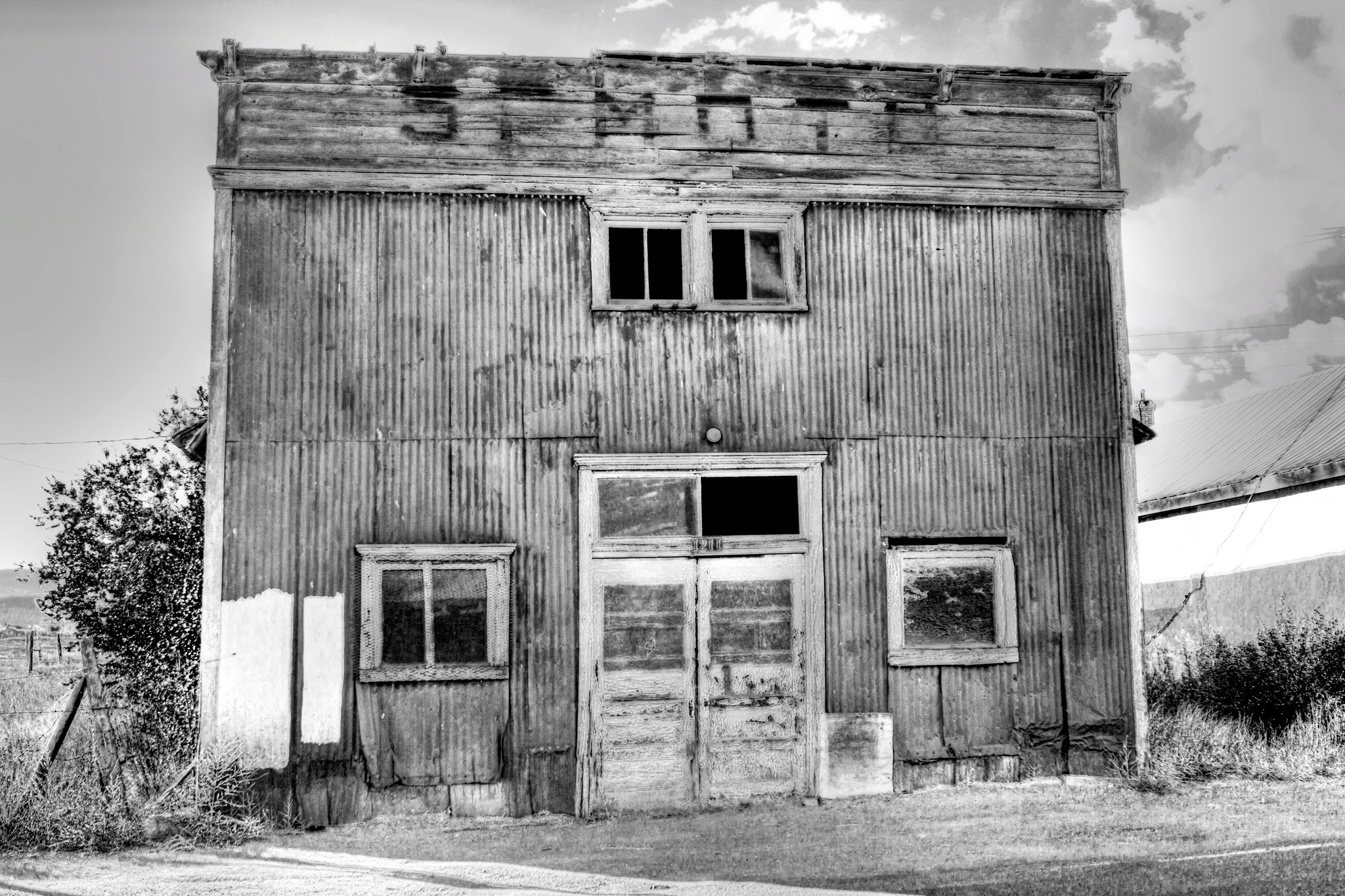

photo by Nicolas Peña

The result was the Sociedad Proteccion Mutua de Trabajadores Unidos (The Society for the Mutual Protection of the United Workers), better known as the SPMDTU. The group first formed in 1900 in Antonito, Colorado. The rules of the society, which was a fraternal order providing health and life insurance for its members, were based on the Society for the Mutual Protection through Law and and on the regulations of the Minor Order of St. Francis.

The founders felt that by organizing formally, they could counteract the discrimination that Hispanics were experiencing. The society spread to San Luis in 1902. By 1915, the idea of the society had spread to New Mexico and it reached a membership of 430 people (196). In Questa, the SPMDTU first occupied a building next to the church; later it moved to a building near the intersection of Rtes 522 and 38. By 1971, the organization had 1096 members. The Questa chapter existed mainly for the insurance aspects of the organization.

Despite such mutual aid groups, this discrimination continued through the early part of the 20th century. In 1936, the Governor of Colorado tried to stop Spanish speakers from coming into southern Colorado and checkpoints for this purpose were at Fort Garland and Antonito (197). Many Colorado restaurants had “White Trade Only” signs.

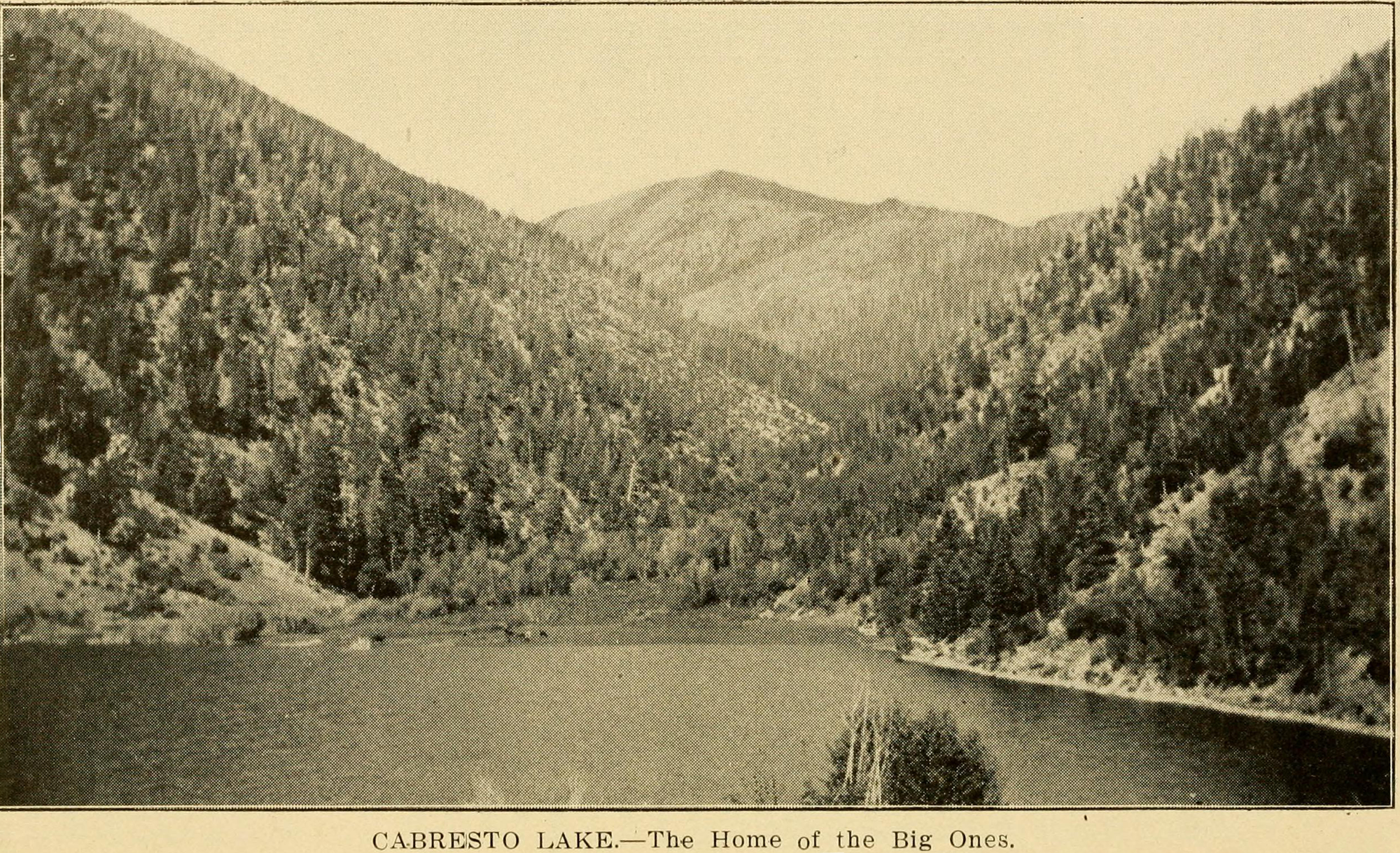

The inhabitants of Questa acted early in the 1900s to protect their water rights. In the case of one of the acequia associations—The Cabresto Lake Irrigation Corporation—Melquiades Rael, Benito Luis Ortiz, Eulogio Rael, Francisco Borja Rael, and Jose Maria Cisneros acted to incorporate and get construction underway for a better system. In the February 13, 1902 articles of incorporation, they described their purpose “…to construct a canal commencing about 6 1/2 miles up the Cabresto River easterly from said Town of Questa, thence westerly down said stream to said Town and continuing therefrom easterly about 2 1/2 miles and appropriating the waters of the outlet of Cabresto Lake.”

The dam at Cabresto Lake was approved by the Territorial Engineer Vernon I. Sullivan on April 10, 1908, and work on the dam was completed in January of 1910. Five ditches were approved by the Territorial Engineer on November 23, 1910. The cost for building the system was $15,000. This ditch association has a priority date of 1815, perhaps coinciding with the first settlement of this area. These water rights were re-registed July 30, 1952, for another 100 years. The corporation was legally extended on July 30, 1956 (see note 204).

Library of Congress

Isolated as Questa was, the town was not spared during the Spanish flu pandemic of 1918–1919. Worldwide, one in five people got the flu and over 21 million died. The first case appeared in Camp Funston, at Fort Riley, Kansas, on March 8, 1918, and the disease spread throughout the world in three waves, with the second between September and December 1918 being the most devastating. Most of the dead fell into the 20- to 40-year age group, thus decimating the strongest people in the community (198). The pandemic seems to have swept through the Questa area between September 28 and October 5th of 1918 (199). On October 11, 1918, all schools, churches, and other public places were ordered closed and people were required to wear gauze masks in public.

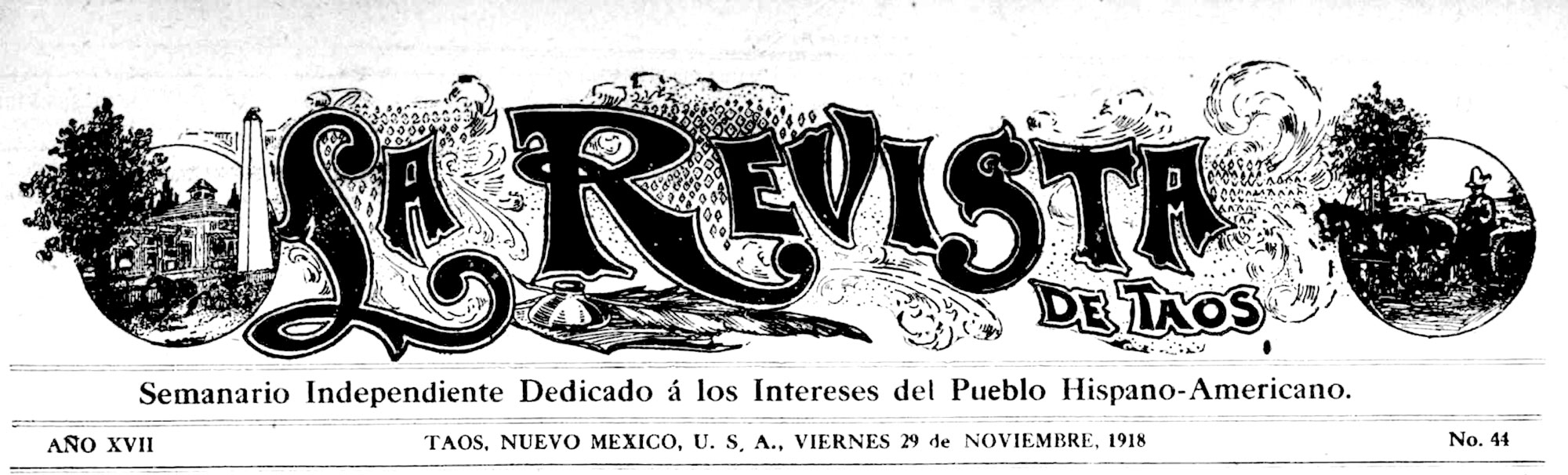

The November 29, 1918 issue of La Revista de Taos (200) lists the 50 or so names of the flu deaths in Questa and Cerro reported by the quarantine official, M.S. Trujillo of Questa. No age group was spared, with the deaths ranging from infants to the very old. About 28% of all Americans were affected by the flu and about 675,000 died. In New Mexico there were 50,000 cases and 5,000 people died, New Mexico was one of the last states to get the flu, and it was suspected that it came into the state with a circus that arrived in Carlsbad on October 8, 1918. Rural New Mexicans towns were hit much harder than the urban areas. Other diseases periodically struck the town, and typhoid existed in Questa until the 1940s.

Questa celebrated its centennial in 1935, and Jose Praxedes Rael (1895–1976) commemorated the event with his poem “The Founders of Questa” (see page 2).

During the Great Depression, small villages such as Questa were able to survive because of extended families working together. In addition, the Works Progress Administration under Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal program provided construction projects in Questa— construction of the road to the Fish Hatchery, the road to Red River, and the La Cienega school.

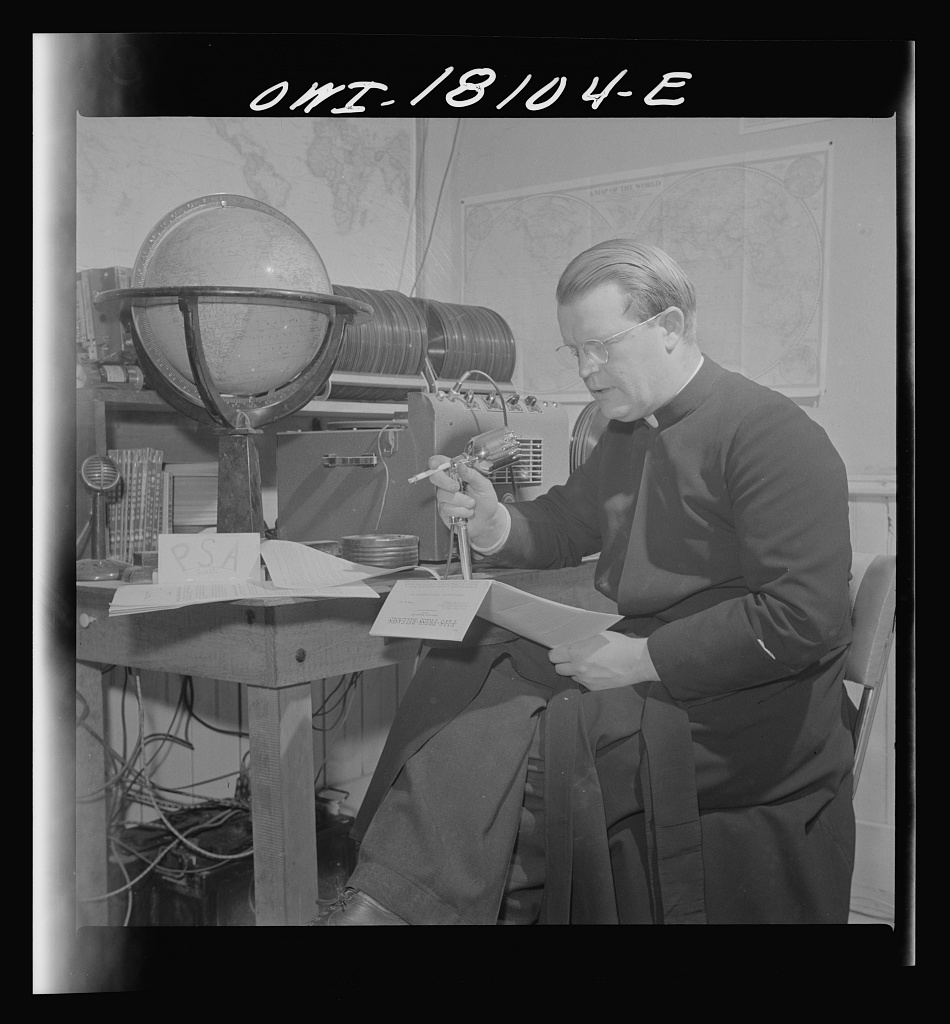

These programs also brought to Questa the Writer’s Project that recorded much of the oral history of the area extant at the time, and people like John Collier documented daily life in Questa through photography. But old ideas died hard, as revealed in the following description of Questa written by Collier in 1943 (201):

“At this time [1943], Questa had the most despicable reputation with anyone else. So Father Smith decided to do something. One day he got an axe and starting tearing down the bridge, the only way out of town. When people saw what he was doing, they were furious. They said, “What are you doing that for?” And Father Smith said, “If I don’t tear down the bridge, it’ll fall down.” The people said, “In that case, we’ll help you.” So they tore it down and then they realized what they had done. “Now we can’t get out of town,” they said. Father Smith said, “I guess you’ll have to build another one.”

And they did.

Father Smith lived in a house on top of a hill where the Parish Hall is now located. From there he could see everything that was going on in town—who was fighting, who was hanging out in bars, and so forth. One day he had a police siren mounted on top of his car. Whenever he saw a disturbance, he’d turn on the siren and go down. He said to them, “Did you see it? Did you hear it? Then swallow it.” He succeeded in remodeling Questa. Two years later it won a prize for civil cooperation.”

Collier, John, Jr., 1943 Library of Congress

Collier, John, Jr., 1943 Library of Congress

As late as the 1940s and 1950s, Questa remained a sheepherding and grazing community with about 5000 sheep. Sheepherding has since declined for a number of reasons, chief among them the fact that sheep carry diseases that affect bighorn sheep. As a result, the

U.S. Forest Service has been converting sheep permits to cattle permits (202).

Questa became incorporated on March 12, 1964, by approval of the Taos Board of County Commissioners (203). The first town election took place in July of 1948.

In 1974 the Cabresto Creek—Red River Adjudication began for the local acequias. This adjudication covers the Cabresto Lake Irrigation Association (which has a priority date of 1815), the Llano Community Ditch, four community ditches that take water from the Red River (Questa Citizens Ditch Association), the acequias that get water from West Latir Creek, and the Acequia Madre del Rito de La Lama.

The purpose of the adjudication was to determine the extent and validity of the water rights and how they would be affected by a reclamation project. These claims were heard by as Special Master of the U.S. District Court in 1990 and some disputed claims were validated, but a final decree has not been issued by the Court for all claims (204). (The Cabresto Lake Irrigation Corporation claim was adjudicated in June of 2002.)

Questa was invaded by “marauders” from the north one last time in 1978. Two motorcycle gangs—the Night Fliers of Liberal, Kansas, and the Sons of Silence from Colorado Springs—came into town over the July 4th holiday weekend and caused enough commotion to force the local businesses to close in Red River and Questa.

The armed bikers then began threatening Questa residents and stopping cars, and there were reports of shots being fired; also there were reports that the bikers threatened to “burn this Mexican town down.” Local police led the bikers to a campground outside of Questa. Men from Questa were then involved in a shootout with the bikers on Route 38.

State Senator C.B. Trujillo stood behind the actions of the Questaños saying they were “doing the only American thing” and that the response was “the only American reaction you can take when you see your community destroyed.” In the end, four bikers were wounded and two Questa men were arrested (205).

Questa today is the sum of many influences—medieval, religious, Spanish, Native American, Anglo, and French. Played against a dramatic landscape of mountains, valleys, mesas, and volcanic terranes, these influences have been combined and adapted to form a traditional northern New Mexican village, where faith, family, and interdependence have blended with the water and the land.

Questaños live on land that was defended by their ancestors—against maurauders and against drought. In many ways Questa remains this traditional Hispanic village of northern New Mexico. Perhaps it is less well known than the High Road villages of Truchas, Chimayo, and Peñasco; nonetheless Questa remains authentic and unique.

Notes

196. Sanchez, Frederick C. A history of the S.P.T.M.D.T.U. The San Luis Valley Historian, vol. III, no. 1, winter 1971, pp. 1-15.

197. The Culebra River Villages of Costilla County, Colorado. National Register of Historic Places. Multiple Property Submission. U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service. Valdez and Associates, 2000 and Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation, Denver, Colorado.

198. Daniels, Rod. In Search of an Enigma: “The Spanish Lady”. National Institute for Medical Research, 1998.

199. Lawrence, E. Spanish ‘flu keeps its secrets. Nature Science Update, 1999. www.nature.com/ nsu/990304/990304_5.html, accessed 5/22/03; Melzer, Richard. A Dark and Terrible Moment: The Spanish Flu Epidemic of 1918 in New Mexico. New Mexico Historical Review 57:213-236, 1982; Spanish flu 1918-1919; www.geo.arizon.edu/Antevs/nats104/oolect24spanishflu.html, accessed 5/22/03; The Influenza Pandemic of 1918. www.stanford.edu/group/virus/uda, accessed 5/22/03.

200. La Revista de Taos, November 29, 1918.

201. Wood, Nancy. Heartland New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1989, p. 82

202. Hedlund, Eric J. Sheepherder fights to keep grazing permit. The Taos News September 14, 2002, p. A12.

203. Questa incorporating—fifteen years ago. The Taos News, March 22, 1979, p. A4.

204. “Life Along the Capillaries—Questa’s Ageless Acequias.” In Dialogue—Agriculture at the Crossroads. The NM Water Dialogue/Western Network and the Natural Resources Center at the University of New Mexico, August 1996, pp. 4-7; Cabresto Lake Irrigation Corporation records.

205. Blair, Billie. Events recalled in Questa, RR area shooting. The Taos News July 13, 1978, pp. A1-A2; Police puzzled by shootout at Questa. The Taos News, July 6, 1978, p. A1; Questa Council meeting, July 10, 1978.