The turn of the 18th to 19th century was a pivotal point in the history of the Questa area. Spanish militia and settlers had finally reached this area still dominated by the Utes, Apaches, and Comanches. French trappers also penetrated the area as did new interlopers—European and American travelers and mappers and the vanguard of the American military.

The first of these outsiders was Zebulon Montgomery Pike, U.S. Army officer and explorer. He was ordered west by Gen. James Wilkerson in 1806 to find the sources of the Red River de Nachitoches and Arkansas River and to explore Spanish New Mexico—really to “approximate” the Spanish possessions, determine what he could about the politics and geography, and hunt the Comanches. After reaching what is now Pike’s Peak in Colorado, he turned south to the Rio Grande, where he was captured by Spanish troops in 1807 and brought to Santa Fe—probably the first American visitor to that city—and then to Chihuahua for questioning.

The Spanish suspected that he was a spy and there is evidence to support these suspicions. Spain was still guarding New Mexico Province carefully and did not want incursions like this from Americans who were seeking the gold that was thought to be in the area. Pike’s book An Account of Expeditions to the Sources of the Mississippi and through the Western Parts of Louisiana was the first written description of this part of North America available to the American public. Did his expedition pass through the Questa area?

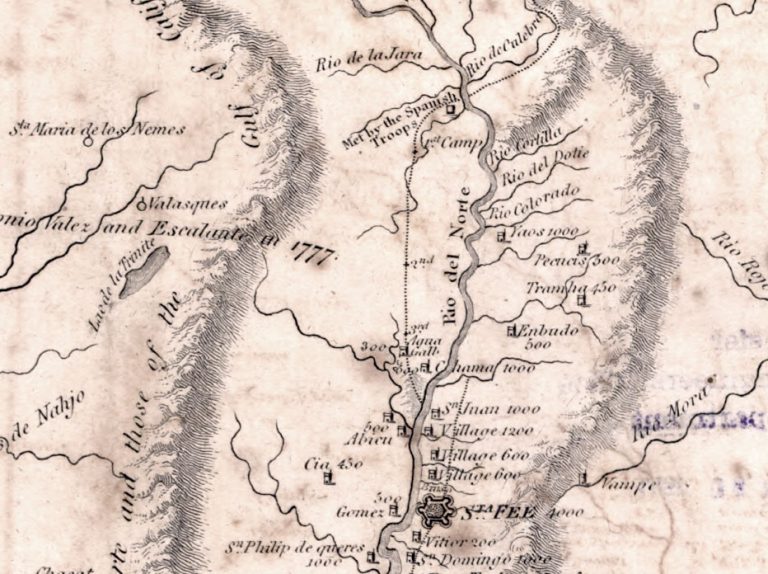

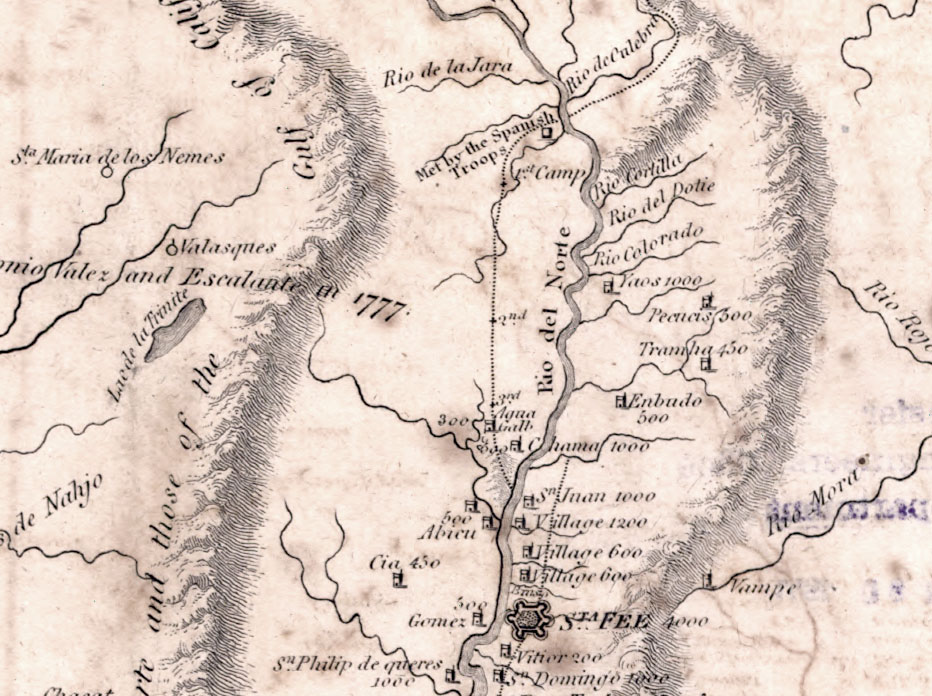

Pike’s map of the area shows the Rio Colorado of this area plainly marked and properly placed. (See Figure 10). He hunted widely throughout the area; however, it appears that Pike traveled south on the west side of the Rio Grande and was captured just south of Alamosa (45).

The Santa Fe trail, from St. Louis to Santa Fe, was first traveled by Americans in 1810. The firm of McKnight & Brady sent the first eastern trade goods to New Mexico that year and their men (James Baird, Robert McKnight, Samuel Chambers, and others) were seized by the Governor of Santa Fe and imprisoned in Chihuahua for 10 years.

The Spanish had been trading with the Utes from as early as 1765, even though they were forbidden by law from doing so. Not only did they trade in furs, but they also engaged in slave trade. However, by the time of the Louisiana Purchase in 1803, the Spanish realized that they needed the friendship of the Indians, particularly the Plains Indians, so that they would be a buffer against the French and Americans and the fur trade was a perfect tool for this (46). Spanish trappers were granted licenses to trap in the frontier areas, but they could not take foreigners with them. To deter the influx of the French and American trappers, the Spanish government established a military post on the Rio Colorado around 1815 (47).

Settlers had started moving up from Taos, first to Arroyo Hondo and Arroyo Seco in 1815 (48) to seek new pastures for herding their sheep and goat. They lived in adobe huts and dug ditches for irrigation. Civilian settlers also tried to establish themselves on banks of the Rio Colorado in the same year. Filed with a Private Land Claims Court case (49) is the following document, evidence of a land grant to people in Rio Colorado in 1815. The original decree of Governor Don Albert Maynez is believed to have been lost, but the following report of Pedro Martin, an officer of the Spanish government, was reported to be in the archives of the Surveyor General as file number 801:

Sir Governor

I report to Your Excellency, that in accordance with your instructions I have proceeded to the place and site of the Rio Colorado, and put fifty families in possession. I notified and gave them to understand that the settlement which they make in the place mentioned must be common, not only for them but for all the residents which in the future may join them. That in reference to dangers said place is exposed to, they should always keep themselves well provided with arms. All answered that they had heard and understood of what they had been notified.

God guard Your Ex’cy many years Taos December 23, 1815Pedro Martin

In testimony given at the Private Land Claims Court case, Juan Antonio Laforet testified that he remembered seeing ruins of the 1815 settlement houses when he was in Rio Colorado in 1842. Francisco Montoya testified that he knew of the 1815 grant (49).

It was this settlement that was described by the next visitors to this area—the Auguste Chouteau—Julius DeMun expedition, who came to New Mexico in 1815-1817. Chouteau and DeMun had hoped to get permission from the Spanish government to trap beaver in the northern New Mexico area. While Chouteau and his men waited at the Sangre de Cristo Pass, DeMun went south to ask for permission to trap on the upper Rio Grande. He described in his journal being stopped at the “frontier village of Rio Colorado” and not being allowed to proceed to Santa Fe. Thus, DeMun’s journal provides the first evidence of any Spanish settlement at Rio Colorado (50).

Chouteau and DeMun were ordered out of Spanish territory; however, they stayed on and in May of 1817 were captured by Spanish soldiers and brought to Santa Fe. These trappers almost had the same fate as the McKnight and Brady expedition. The Spanish imprisoned them for 44 days and confiscated all of their property—$30,380.74 1/4, “the fruits of two years’ labor and perils” (51). Then they were set free, each with a horse, and they returned to St. Louis.

An 1817 census for the Province of New Mexico shows a total of 36,579 people—18,276 Spanish, 9422 “Indios” and 8881 “Idem de carras.” On the west side of the Rio Grande, Abiquiu and Ojo Caliente had initially been settled as early as 1747. Although driven off by Indian raids, settlers reoccupied Abiquiu in 1754 and by 1808 it numbered 2000 people. Ojo Caliente was resettled in 1768–1769. Settlements north of Rio Colorado in what is now southern Colorado were attempted as early as 1788 and again in 1833, but settlement north of Rio Colorado would not begin in earnest until the granting of the Las Animas Grant to Charles Bent (52).

Indian attacks were a continuing problem and the Mexican government set up the Provincias Internas to deal with these problems on the northern frontier. Using more experienced soldiers, the government plan was to impress upon the Indians the Spanish military strength and at the same time to emphasize that the goal was friendship. To help this along, they gave the Indians firearms and liquor to make them more dependent on Spanish goods.

The arrival of Anglo-Americans from the east was a continued threat to the alliances being made with the Indians. Tyler points out in his article on Mexican Indian policy in New Mexico (53) that during the early 1820s the Mexican government considered the Indians to be equal to the white man in rights and privileges, something the frontier settlers did not support.

Traders were now beginning to move up and down the Taos, or Trappers, Trail, which came from Santa Fe to Taos, north through the San Luis Valley and then over the Sangre de Cristo Pass to the Arkansas River. Four forts were established on the Sangre de Cristo Pass in 1819 to guard the eastern approach to New Mexico against foreigners. The fort on the eastern side of the pass lasted for one summer, and then was attacked and destroyed by “three hundred Indians or white men dressed as Indians” in October of that year (54).

Other evidence collected by Major Stephen Long’s Rocky Mountain expedition in 1820 seems to indicate that the fort was attacked by Pawnee Indians from the east (55). The Sangre de Cristo Pass had long been the Comanche war path to northern New Mexico and the Questa-area settlers and it was also a hunting road for the Utes to the buffalo on the plains east of the moutains. The Santa Fe Trail, established in 1821 went over the Raton or Cimarron Passes to Santa Fe.

Despite this increased traffic on the Taos Trail, by 1822 the settlement on the Rio Colorado seems to have vanished. This area was visited by Major Jacob Fowler, a land surveyor, under Col. Hugh Glenn on February 6th, 1822, on the journey from Pueblo to Santa Fe (56). In his journal (57), Fowler describes in his own colorful language and unique spelling what was left of the settlement… “on this Crick there Is a Small Spanish vilege but abandoned by the Inhabetance for feer of the Indeans now at War With them We this day troted the Horses more than Half the time and maid thirty miles not did We Stop till In the night.”

Just to the north, Fowler had camped a few months earlier with Kiowa Indians in a camp of over 4000; while he was there, 300 lodges of Comanche arrived as did 350 lodges of Comanche, Kiowa, Padduca, Cheyenne, Snake, and Araphahoes. He describes a camp of 900 lodges with 10,000 to 18,000 Indians and 20,000 horses—it was no wonder that the hardy settlers at Rio Colorado were driven away! (58).

But trade on the northern frontier continued to be encouraged by the Utes. Thomas James, who was with the Missouri Fur Company and in New Mexico in 1821 (59), described the Ute trade with New Mexicans. James desribed a speech by the Ute leader Lechat urging trade:

“Come to our country with your goods. Come and trade with the Utahs. We have horses, mules and sheep, more than we want. We heard that you wanted beaver skins. The beavers in our country are eating up our corn. All our rivers are full of them. Their dams back up the water in the rivers all along their course from the mountains to the Big Water. Come over among us and you shall have as many beaver skins as you want.”

As for the Spanish in the area, Lechat said:

“What can you get from these? They have nothing to trade with you. They have nothing but a few poor horses and mules, a little puncha, and a little tola [tobacco and corn meal porridge] not fit for anybody to use. They are poor—too poor for you to trade with. Come among the Utahs if you wish to trade for profit. Look at our horses here. Have the Spaniards such horses? No, they are too poor. Such as these we have in our country by the thousands, and also cattle, sheep and mules. These Spaniards, What are they? What have they? They won’t even give us two loads of powders and lead for a beaver skin and for good reason, they have not as much as they want themselves. They have nothing you want. We have everything they have, and many things they have not.”

Americans visited the Questa area again in July 1825 when George Sibley, who was sent by the U.S. Secretary of War James Barbour to assess the Indian tribes, arrived at the New Mexico border. Spanish authorities turned most of his party back, but Sibley was given permission to travel to Taos, where he arrived on October 31, 1825. In July of 1826, the Mexican government gave him permission to survey a road from the east to Santa Fe. As for his assessment of the Indians, he wrote “With the exception of the Pawnees, the tribes that have been mentioned have but little knowledge of our Government and People; and none of them have any Respect for the Mexican authorities” (60).

The American and French incursions continued and during the 1820s, their trapping led to the use of beaver pelts as a form of currency. People living on the northern New Mexican frontier were cash poor and they needed money to buy any type of manufactured equipment and supplies. Trapping was one means; another was raising sheep. By 1827, there were an estimated 250,000 sheep in the northern frontier area. These could be sold for hard cash as well, although that meant making a very long 40-day trip to Chihuahua (61).

In an 1829 military expedition to the Questa area (62), Donaciano Vigil describes what was left of the settlement on the Rio Colorado (63):

“In the year 1829, as military commander of about two hundred men, I being of them as sergeant, on our way home to have a council and to make a treaty of peace with the Northern Indians, who had re-commenced hostilities recently, passed by the place mentioned, the town of Rio Colorado. It was abandoned in consequence of depredation of the Indians, and was a square of houses of about fifty varas on each side, the walls of the houses being all standing. I was never at the place again. The place stands on the north bank of the Rio Colorado, about five or six leagues north of Don Fernando de Taos.”

In addition to the Col. Hugh Glenn and Jacob Fowler trapping expedition and the Thomas James and John McKnight forays into New Mexico, trappers active in this area in the 1820s included General William H. Ashley, Smith, Jackson, Sublette, the Rocky Mountain Fur Company, and Astor’s American Fur Company. (David J. Weber’s book The Taos Trappers

[64] is an excellent source of information about the trapping industry in this area.)

This increasing flood of French trappers and Americans from the east would change the relationship of the Mexican frontiersmen with the local Indians—up until this time the Spanish used the commercial dependency of the Indians. Yet the governor of Chihuahua thought that the arrival of the Americans might have a good effect. In 1825 he said that contact with the Americans “would produce the advantages of restraining and civilizing the New Mexicans, giving them the idea of culture which they need to improve the disgraceful condition that characterizes the remote country where they live, detached from other peoples of the Republic….” (65).

These early settlers in Rio Colorado were indeed “detached” from the Republic. In 1828, about half of the Church parishes in New Mexico had no priest. A parish on the frontier meant isolation and danger. Many of the churches existing churches were crumbling, and, because the Franciscans had left New Mexico, many parishes saw their priest only a few times per year. (66)

Notes

45. Coues, Elliott (ed). The Expeditions of Zebulon Montgomery Pike to the headwaters of the Mississippi River through Louisiana Territory, and in New Spain during the years 1805–6–7, pp. 492–510, 704–705, maps.

46. Weber, David J. The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540-1846. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1968, 1970.

47. Simmons, Virginia McConnell. The San Luis Valley: Land of the Six-Armed Cross, 2nd ed. University Press of Colorado, 1999

48. Cheetham, Francis T. The early settlements of southern Colorado. The Colorado Magazine 5, 1, 1928.

49. Cañon del Rio Colorado grant, SANMI roll 49, case 166, Private Land Claims Court. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe.

50. LeCompte, Janet. Jules de Mun. In LeRoy Hafen (ed.). The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, vol VIII, pp. 95-105. Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, CA, 1971.

51. Ulibarri, George S. The Couteau-DeMun Expedition to New Mexico,l 1815-17. New Mexico Historical Review vol XXXVI, pp 263-273

52. Spanish Archives of New Mexico, Series I (SANMI) roll 188 1815-1817, frame 870, New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe, NM. 52. Ulibarri, George S. The Chouteau-DeMun Expedition to New Mexico,l 1815-17. New Mexico Historical Review vol XXXVI, pp 263-273

53. Tyler, Daniel. Mexican indian policy in New Mexico. New Mexico Historical Review 55:101- 120, 1980.

54. Colville, Ruth Marie. The Sangre de Cristo Trail. The San Luis Valley Historian, vol III, no.l 1, 1971, pp. 11-33.

55. Thomas, Chauncey. The Spanish fort in Colorado, 1819. The Colorado Magazine XIV, 81-85, 1937.

56. Williams, George A. A condensed interpretation of Jacob Fowler’s record of 1821 events in southeastern Colorado. Pueblo County Historical Society, http://www.pueblohistory.org/history/ fowler%20jeweler.htm.

57. Coues, Elliott (ed). The Journal of Jacob Fowler: Narrating an Adventure from Arkansas Through the Indian Territory, Oklahoma, Kansas, Colorado, and New Mexico to the Sources of the Rio Grande del Norte, 1821-22. Francis P. Harper, New York, 1898.

58. Williams, George A. A condensed interpretation of Jacob Fowler’s record of 1821 events in southeastern Colorado. Pueblo County Historical Society, http://www.pueblohistory.org/history/ fowler%20jeweler.htm.

59. James, Thomas. Three years among the Indians and the Mexicans, Printed at the office of the “War Eagle,” Waterloo, Illinois, 1846; Weber, David J. The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540-1846. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1968, 1970.

60. Gregg, Kate Lelia. The road to Santa Fe: the journal and diaries of George Champlin Sibley and others pertaining to the surveying and marking of a road from the Missouri frontier to the settlements of New Mexico, 1825-1827. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1952.

61. Weber, David J. The Mexican frontier, 1821-1846: the American southwest under Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1982.

62–63. Cañon del Rio Colorado grant, SANMI roll 22:447 SG 93. Surveyor General’s Office. New Mexico State Records Center and Archives, Santa Fe.

64. Weber, David J. The Taos Trappers: The Fur Trade in the Far Southwest, 1540-1846. University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1968, 1970.

65. Weber, David J. The Mexican frontier, 1821-1846: the American southwest under Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1982.

66. Weber, David J. Myth and History of the Hispanic Southwest. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1988, pp 105-116.