Mining would play an increasing role in the life and economy of Rio Colorado/Questa. The first Rio Colorado connection with the copper and gold rush in the Moreno Valley was William Kronig, who had lived and did business in Rio Colorado in the 1850s.

A few Indians had brought colored rocks to Kronig and Captain William Moore at Fort Union in 1866. Kronig and Moore sent two men to investigate the source of these rocks, Mt. Baldy, and they indentified them as copper. Four men were then sent to Mt. Baldy by Kronig and Moore to do the necessary work so that the claim could be filed and certified as the Mystic Copper Mine. While there, one of the men discovered gold while panning in Willow Creek, and the gold rush was on (186) by the spring of 1867.

Kronig, Moore, Lucien Maxwell, and others formed the Copper Mining Company and when work started on the copper mine in 1867, they found more gold. By the spring of 1868, there were more than 3000 people working the gold fields and living in the new town Elizabethtown. By 1899, about $3 million worth of gold had been mined in the Baldy area (187).

By the end of the 19th century, mineral deposits were found much closer to Questa; in the late 1880s, two prospectors found a metallic material in Sulphur Gulch. They did not know what it was but they staked a claim anyway. And to add to the Red River confusion, a new town of Red River, up the road from the old Rio Colorado settlement, was established in 1895 after the discovery of gold in the area; that town’s population ballooned to over 2000 in 1897 (188).

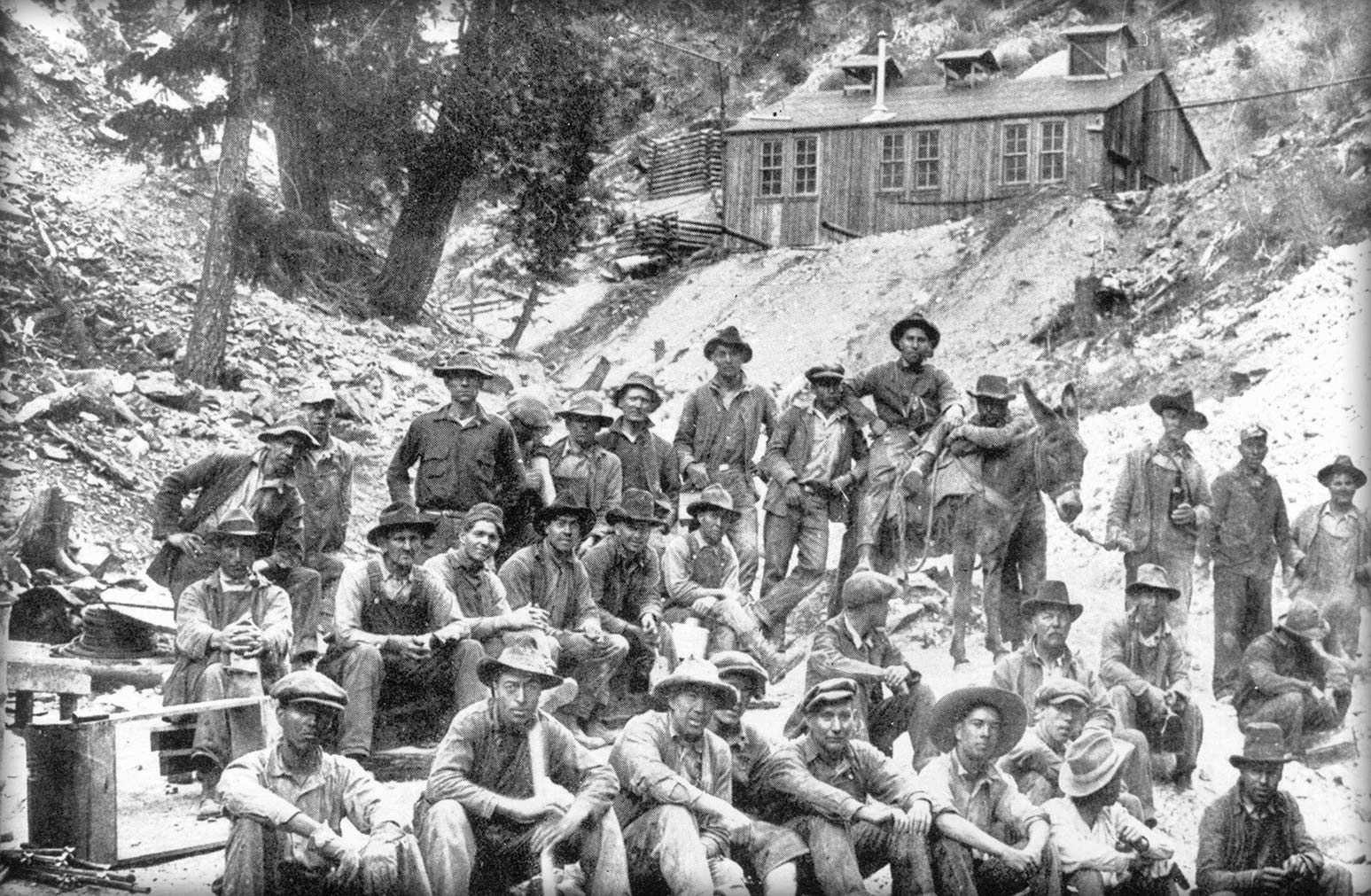

Gold mines such as the Midnight, Anchor, Caribel, Edison, and Memphis mines were close to Questa and were worked in the 1890s; the small, albeit short-lived, towns of Midnight and Anchor sprung up at the sites of these mines. Unfortunately, ore had to be sent to Denver for treatment, and this along with legal issues regarding the land on which the mines were located resulted in their abandonment after only a few years of operation. Other short-lived mining towns in the area included La Belle, Hematite, and Amizette. Gold, silver, iron, and copper were mined to the northwest of Questa in the San Luis Valley throughout the 1880s and 1890s, one of the most productive mining towns in this area being Creede.

Several placer gold sites were located near Questa, and Questa served as a shipping point for many of these mines. (Placer mining was done by panning or with sluice boxes, which separated minerals that had washed down from the mountains from the mud of creek beds.)

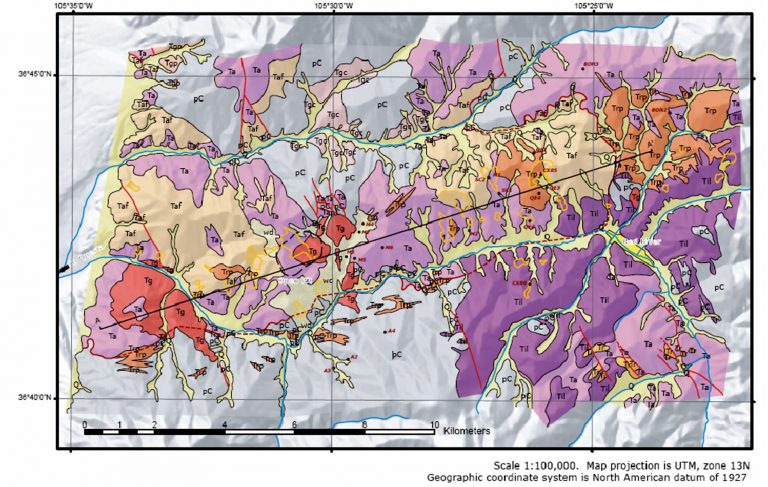

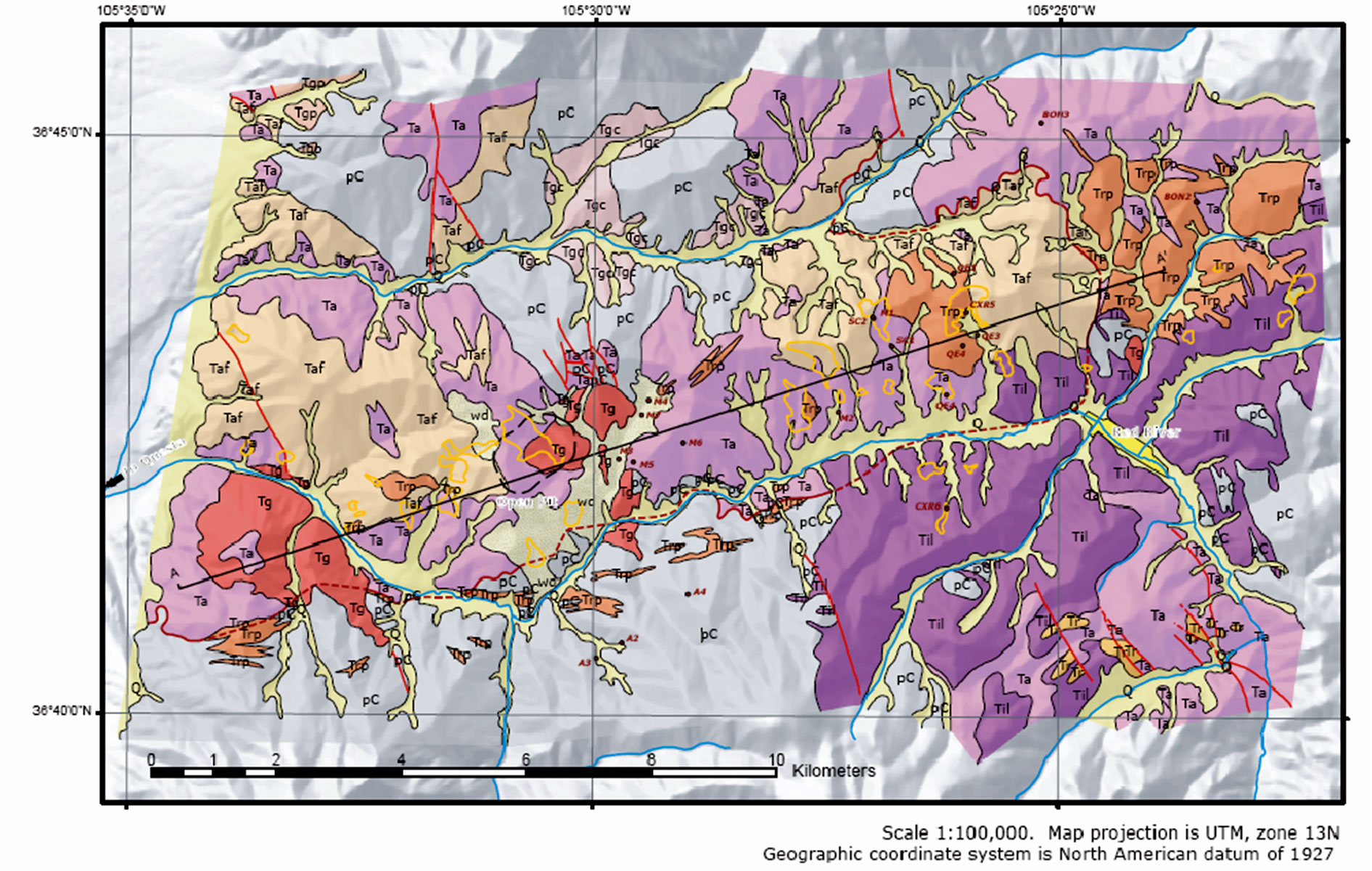

During World War I, molybdenum was used to harden steel and this use enabled the identification of the ore found in Sulphur Gulch. The molybdenum was formed in the volcanic activity of 25 millions years ago that formed the Questa caldera. A prospector named Fahy sent samples of the molybdenum to an assayer, thinking it was silver; the assayer identified the presence of molybdenum in the sample. In 1920 the Molybdenum Corporation of America bought the Sulphur Gulch claims by federal land patent under the Mining Law of 1872 (189) and began underground mining (1922-1958) at the site.

The original underground mine had over 35 miles of tunnels, and the ore was sent to a gold mill near Red River for processing. A processing mill was built at the mine site in 1923. By the 1950s, a company town had been established near the mine and the mine was the second largest supplier of molybdenum in the United States. Open pit mining followed (1964-1985), and in 1985 a more extensive underground mining operation began to reach the Goat Hill ore body. These workings are 2000 feet below ground and a 7000-foot decline shaft is used to bring the ore up to the mill for processing (190).

With the arrival of this new mining-based cash economy, people in Questa suddenly had a new way to make a living as miners. By the 1980s, the Moly Mine employed almost 600 people (191), but this was a boom-or-bust-based economy with work at the mine dependent on the world market for molybdenum. Decades of mining have produced 328 million tons of waste (191) at the mine site and 100 million tons of molybdenum ore.

Spills from the tailings pipelines and acid drainage from the mines waste sites have apparently contaminated parts of the Red River and local acequias, and dust from the tailings have been shown to have high levels of lead, zinc, cadmium, arsenic, and mercury. Thus, while Molycorp, which disputes claims of pollution, has pumped some $30 million per year into the local economy, the environmental issues relating to the mine have been taking an increasing role. Action by environmental groups under the Clean Water Act have brought in state and federal regulation of the mine operations and the institution of reclamation procedures.

Mining and the news of gold and silver strikes also brought in large numbers of people from the outside, and in some cases trouble. One of the most famous examples of this was the murder of 19-year-old James Redding by John Conley near Questa at the Guadalupe placer claims on January 16th, 1905.

As stated in the true bill of murder, Conley was accused of “…unlawfully, feloniously, willfully, purposely, of his deliberate premeditated malice aforethought shoot off and discharge at upon and in the forehead of him the said James Redding and in the throat of him the said James Redding…inflicting in and upon the forehead…about one half an inch to right of the center of the forehead…the bones of the top and back of the head being broken by said bullet, one mortal wound…and inflicting in and upon the throat of him the said James Redding, immediately above the larynx, one mortal wound, of which said mortal wounds the said James Redding then and there instantly died” (192).

In a legal document of the First Judicial District of the Territory of New Mexico, Conley claimed that he was protecting his mining claim from Redding, who had advanced upon the defendant, “…cursing, abusing and threatening to take his life, with an axe uplifted and ready to strike.” In an undated appeal (193), Conley argued that during his trial, in which he was convicted, no evidence was presented to dispute his story.

Redding was said to be “…under the influence of liquor” and Conley said he went “…to Questa and Red River for the purpose of surrendering himself to the authorities…” although not immediately “…due entirely to his fear.” Redding’s father had a hotel in Questa and Conley knew him and the family well. Conley also shot one Charles Purdy, 70 years old, “…who was advancing towards him with an uplifted axe….” The jury’s verdict was not unanimous—at least one juror when polled said “It was the best we could do” (see note 192).

Conley’s appeal to the Supreme Court was denied and his sentence to death by hanging stood. In a newspaper report of January 25th, 1906 (194), Conley still held to his innocence “Even should I hang for this affair, I now, with my last breath, will maintain that I shot to save my own life. The killing was brought about in such a manner that I could not act other than I did.”

He further describes the scene: “Purdy and Redding had been drinking….. We quarreled over the terms of a contract which I had made for doing assessment work on the placer claims. Purdy ordered me to leave the tent, and emphasized his remarks by throwing a heavy iron frying pan at me…I backed away from the man and walked down a narrow path to where our horses were tied, intending to mount and ride to Questa. Purdy came from the tent and took an axe which was sticking in a nearby log and followed me. Redding, in the meantime, secured another axe from the same log and took a short cut to the horses.”

Conley then described how he drew his .38 revolver from his waistband and shot Redding in the forehead and the throat and struck Purdy in the chest.

He then rode to Questa: “I intended to give myself up there, but when I reached the town I was afraid that I would not be treated properly by the officials. After spending a few moments in a store at Questa, I rode to Red River.” But before he could talk with the Justice of the Peace there, a posse from Questa arrived and he was brought back to Questa. Conley claimed that he could not get a hearing from the Supreme Court because he lacked the funds to have a transcript made of the Taos Court proceedings.

So John Conley became the first person to be hanged in Taos County under the Territorial Government between 1848 and 1906. Because of the ruthless administration of justice following the Taos Rebellion in 1847, Taos juries were loathe to return death penalty verdicts. But Conley did not benefit from such jury reluctance. His hanging took place in 1906, but Conley protested to the end in his own way and did not get the swift and sudden death that he had meted out to Redding and Purdy. Just before the hanging Conley somehow got a rusty pocket knife and tried to slash his throat. He failed to cut an artery, although he suffered a heavy loss of blood, and a doctor treated his wounds.

While he was still unconscious from this suicide attempt, he was taken to the gallows, seated on a stool with a noose around his neck, and hanged. Unfortunately, the drop did not break his neck and he died a slow death from a combination of strangulation and blood loss (195). Robert J. Torrez in his article on lynchings and legal hangings in the NM Territory notes that professional hangmen were not used in New Mexico and that executions were carried out “…by understandably nervous public officials who frequently bungled the task….”

Notes

186. Looney, Ralph. Haunted Highways: The Ghost Towns of New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1968.

187. Sherman, James E. and Barbara H. Ghost Towns and Mining Camps of New Mexico. Univesity of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 1975.

188. U.S. Forest Service—Carson National Forest, USDA. Placer Creek mining history trail; Pioneer Canyon trail, mining history of Red River.

189–190. Bauer, D.W., Love, J.C., Schilling, J.H., and Taggart, J.E., Jr. The Enchanted Circle—Loop Drives from Taos. NM Bureau of Mines & Mineral Research, Socorro, NM, 1991.

191. Atencio, Ernest. The mine that turned the Red River blue. August 28, 2000. High Country News, vol. 32, issue 16.

192. Territory of New Mexico v. John Conley. Murder, a true bill. March 16, 1905. Criminal case # 914. Taos County District Court. NM State Center for Records and Archives.

193. Territory of New Mexico v. John Conley. District Court of the 1st Judicial District of the Territory of New Mexico, Santa Fe County. Undated appeal of trial verdict. NM State Center for Records and Archives

194. Particulars of the killing of Redding, for which the Supreme Court says John Conley will have to hand. January 25th, 1906, unknown newspaper.

195. Torrez, Robert J. Capital punishment in New Mexico. La Cronica de Nuevo Mexico, issue 55, November 2001. Historical Society of New Mexico; Torrez, Robert J. Myth of the hanging tree: lynchings and legal hangings in Territorial New Mexico. La Cronica de Nuevo Mexico, issue 44, January, 1997.