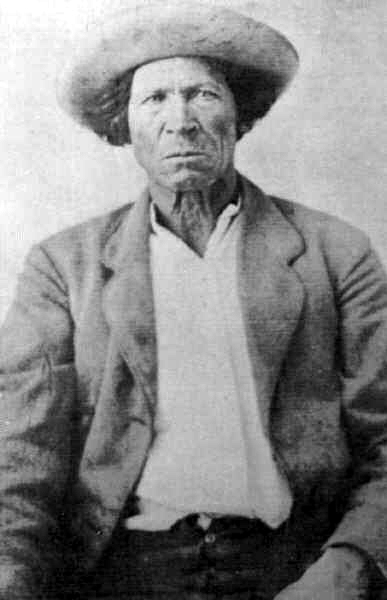

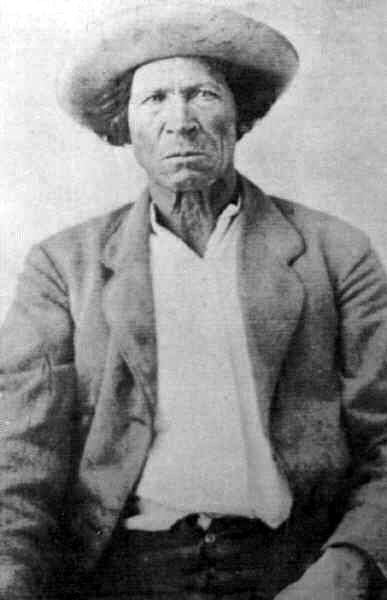

The presence of Francisco Laforet in Rio Colorado drew other trappers and traders to settle in this valley. One of the most colorful, and famous, of these was Charles Autobees, who had many wives and many ways of spelling his last name (Ortibi, Otterby, Ortubus, Ortivis, and Hortuvis being just a few of them). He was the half-brother of Tom Tobin, another famous character in northern New Mexico (155).

Charles Autobees came west from St. Louis as a trapper around 1825. He came to Taos in 1834 or 1835 and stayed to work for Simeon Turley at his distillery on the Rio Hondo where the infamous Taos Lightning was manufactured. Autobees traveled up and down the Taos Trail for Turley, selling his whiskey and flour. Turley also had a store in the new settlement of Pueblo, Colorado, from 1842.

Charles Autobees

The name of one Carlos Hortuvis appears in the list of settlers on the 1842 San Antonio del Rio Colorado land grant; this is presumably Charles Autobees. In 1845, Charles and Tom were granted land at what is now La Lama by the governor of New Mexico Manuel Armijo to help defend it against the Navajos, Utes, Comanches and Apaches. This land, the Cebolla grant, was bordered on the north by the Rio Colorado, on the south by San Cristobal Creek, on the east by the mountains, and on the west by the rocky bluffs of the Rio Grande (156).

Over the next several years, Charles would move back and forth between what is now Pueblo, Colorado, and Arroyo Hondo. He moved up to Rio Colorado in July of 1850 to farm his part of the Cebolla grant. He also worked as a guide for U.S. troops going out after the hostile Indians plaguing the northern settlements. He apparently was a spy for Lieut. J.H. Whittlesey’s March 1849 expedition to “chastise” the Utes (157). Later that year he sold his share of the Cebolla grant to Jose Gonzales.

Lecompte describes Rio Colorado at this time as “New Mexico’s most northerly and hence most Indian-plagued settlement.” In 1853 he went with William Kronig (see below), Marcelino Baca, and a party of 25 men to settle the Vigil and St. Vrain grant at what is now Pueblo, Colorado. He was back in Rio Colorado two months later and in June of 1853 met G.H. Heap (see below) when he visited Rio Colorado. Eventually he settled up in Colorado, where he died in 1882 (158).

1827-1900

A picture of life in Rio Colorado in the early 1850s is provided by the reminiscences of William Kronig (159), who lived in Rio Colorado during this period. Kronig was a German who came west on the Santa Fe Trail to New Mexico in 1849 in hopes of joining Fremont’s troops and to dig for gold in California. In Santa Fe Kronig met up with Viereck (no first name given by Kronig) who painted theatrical scenery and was the brother of a famous German actress, and another German named Schlesinger. They decided to join the territorial volunteer troop of Col. Benjamin Lloyd Beall and headed north to Taos, where Kronig served as Orderly Sergeant and Commissary Sergeant of the Company for two months. Beall’s company was sent up to Rio Colorado to protect the settlers from the Ute and Apaches raids. Kronig describes the settlement (159):

“ We were stationed at a little Mexican town on the banks of the river. The natives had small farms to supply their needs. Their flocks of sheep and goats grazed on the hillsides under the care of a herder. The cattle and horses roamed nearby the settlement, grazing. It was in Rio Colorado that I met La Port [he probably means Laforet], a Canadian-Frenchman, who had settled there.”

In December of 1849 Kronig decided to take “La Port” up on his invitation to spend the winter at Rio Colorado. While hunting game for Christmas dinner, Kronig got the idea to sell game in Taos to the U.S. troops. But Col. Beall decided to send Kronig up to the San Luis Valley to ask the Utes to come to Taos to make peace. He found the Ute camp 7 days past Mosca Pass and obtained a promise from Chief Chico Belasquez to “Tell your Chief that we will come to Taos as soon as the grass is long enough so that it will keep the horse strong; also that we will kill no more Americans and Mexicans.”

After returning from this adventure, Kronig was sent by Beall to Rio Colorado to spy on an Apache Indian married to Mexican woman. Beall thought this Indian was providing information about troop movements to the Indians. Kronig spent a month in a cabin in Rio Colorado watching this Indian but never saw any interaction with other Indians.

Next James H. Quinn, a beef contractor in Taos, asked Kronig if he would like to be set up in business in Rio Colorado. Quinn would supply the goods for sale and Kronig would have to find a suitable building for a store. And so he became one of the earliest storekeepers in Rio Colorado. As he put it, “I had some competition but was satisfied with a fair profit, and in a short time had most of the business.” He further described life in Rio Colorado:

“ This village was very quiet as there was yet no mail route established between Rio Colorado and Taos, or any newspapers. The distance between these two towns was only 30 miles but there were so few people in this community who could read or write, so we had to go to Taos for our mail and reading material.”

Kronig described the physical set up of the village:

“The town of Rio Colorado was built on high ground. A large valley extended to the east, there were meadows and farm lands. Opposite the town, where the valley widens out to the west, the river came out of a deep canyon; at this point is where the La Port farm was located. LaPort had resided there for many years with his family, including his two sons and his son-in-law. They managed their ranch as well as performed the major part of the farm labor. …These four men were, at all times, armed with their Hawkins rifles; even when they irrigated the fields they carried their weapons and also, a good supply of ammunition. In this community it was necessary for everyone to be able to muster a rifle or handle bows and arrows.”

For a change, the Indian situation was quiet:

“Owing to the great depth of snow in the mountains, the Indians had been quiet; no crime had been committed in the vicinity. They had operated on the east side of the mountains, stealing and killing where-ever the opportunity presented itself.”

But this quiet was not to last for long. Indians came into the village and robbed the grain mill and took horses and cattle. Kronig followed the marauders with Judge Beaubien’s nephew (probably John Bautiste Beaubien [160]), who had lost 12 head of cattle to the Indians. They had no luck in retrieving the cattle, which the Indians were killing and eating along the way, and Kronig returned to Rio Colorado.

Then Kronig described a most interesting Indian attack.

“ The Indians were already on the hilltops; the horses and mules belonging to the community were moving toward the canjoy, where the La Ports opened fire, wounding two Indians at their first volley. The Leaders dismounted, picked up their two wounded men and carried them off, leaving the horses and mules they were driving. One of the Indians, more daring than the rest, was completely cut off by the town people and surrounded. I took a careful aim at him and was in the act of pulling the trigger, when someone pushed my gun up and the ball went into the air. “For God’s sake, don’t kill him; he is the son of the rich Juan Vigil.”

I could not see that that fact made any difference, as he was in a sense an Apache Indian. He wore the same dress and acted like them and fired on his own countrymen. I believe he would have killed some of his own people if his aim had been straight…. This man was known as “The Gente, Son of the Rich,” who knew how to read and write; but preferred the company of the Apaches to his own race. He had committed depredations, murder, robbery and torture on his own people, but because he was the sone of the rich Juan Vigil, was not punished.”

Apparently “the rich Juan Vigil” was Juan Benito Vigil, one of the original Rio Colorado settlers. Kronig goes on to tell that robbery and murder by Apaches was quite frequent. “They would sneak in quietly, drive the stock away and if a herder protested they would kill him. Many times the herders would be taken with the stock, never to be seen again.” Kronig soon turned to farming on a borrowed piece of land. Here Kronig was introduced to the peon law, when the son of Isidro Trujillo stole corn from Kronig’s crop. The boy belonged to Rodrigo Vigil, who was one of the richest men in town. Peons earned about $2.50 per month in hopes of cancelling their debt to their owner, usually an impossible goal. Most of them remained in this servitude for the rest of their lives. Because Vigil was charging more than the legal 6 per cent interest in the case of the Trujillo boy, Kronig was able to get the boy released.

It is from Kronig’s account that the story of how to determine the value of a house in Rio Colorado originated. He explained that each joist in the house was worth a dollar and no account was taken of the value of the land. If the house was made of split logs covered with split cedar, then these houses were valued at two dollars per joist.

Justice in the village was administered by the Alcade, who in one instance ordered a thief to be whipped in the middle of the street and then escorted out of town.

Kronig describes how the Church collected taxes on the local people. They collected one-tenth of all the farm goods and one-hundredth of the lambs and calves. There was a tax on every household of one barrel of corn, one-half fanega of wheat, and the expense of an annual Saint’s feast. This system of taxation ended after the annexation of the Territory by the United States.

Kronig’s account also tells the story of a painting for the church. Viereck, who was also living in Rio Colorado, reproached the villagers for having a church with no paintings or other adornments and he offered to paint the twelve apostles on canvas for a payment of $160. The money was raised quickly and Viereck produced the painting, which was hung in the church. Kronig says that “Years later, when I returned to Rio Colorado, the picture was still on the altar of the church.” Viereck is said to have also painted a picture “Christ on the Cross” for a church in Taos.

Kronig described another incident regarding the local Indians. Woken by Charles Autobees shouting “the Apaches are coming,” Kronig went to the main street where La Port [Laforet], Beaubien, and others were already posted at the adobe wall with their rifles. A long string of mounted Indians was approaching, and “as they approached, we noticed that the first ten riders were not Apache Indians but part of a Ute tribe that was at peace with the Americans and Mexicans…we could see that the Utes carried a Mexican wood chopper in front of them for a shield….The Utes…yelled for us not to shoot as they had come in peace; that they, with the Apaches, were on their way to Taos to sign a treaty of peace.”

In total, 120 Apaches and 10 Utes went to the house of the Alcade and asked for peace. The Indians were also well supplied with gold and in a short time they bought out all of the stock in Kronig’s store. He rode to Arroyo Hondo for more goods; in all, the Indians spent about $1200 in Rio Colorado—a small fortune. These Indians were later attacked by volunteer soldiers who confiscated much of these goods. The Utes often came into the village to buy grain and ammunition in trade for animal skins and buffalo robes and Kronig went with the Utes to other villages to trade his own goods.

By 1851, Kronig felt he could make a living trading with the Indians and decided to close up his store in Rio Colorado. After a few trading trips, Kronig decided to settle as a farmer in Cuerno Verde (Greenhorn) in Colorado (sometime between 1851 and 1853). After a trip to Laramie, Wyoming, to obtain cattle, Kronig instead settled at the mouth of the Fountain River, the site of present-day Pueblo, Colorado, where a Mr. Baca (Marcellino Baco of Rio Colorado) had already settled.

Kronig again established a store, but trouble with the Indians culminated in a massacre at Pueblo on Christmas day 1854, in which Kronig’s holdings were destroyed. He went to La Costilla, where he established another store and a distillery, and then moved to Mora near present-day Watrous in 1856 to ranch. With the discovery of gold in the Moreno Valley area in 1860 (see below), for which he was partly responsible, Kronig became a wealthy man. He lost his fortune in a plan to construct a 40-mile ditch and flume and then regained it from a smelter he built in the Magdalena Mountains. He died in 1896.

John Bautiste Beaubien, a nephew of Judge Charles (Carlos) Beaubien was now living in Rio Colorado. On June 1, 1854, he sold a house and land to Solomon Beuthner of Don Fernando de Taos. The property is described as (160):

“Lot bounded on the north by a house and lot now in possession of Francisco Laforette, on the east by the west line of the public plaza of said town, on the south by a house and lot belonging to John Bautiste Beaubien, and the west by a ditch and the public road running on the west side of said town. Said lot or parcel of land being varas in length from east to west and varas in width from north to south and containing one dwelling. This property is located next to the public plaza of the Church.”

The coming of Solomon Beuthner to Rio Colorado was indicative of a new trend in the area—the arrival of German-Jewish businessmen. In 1850, of the 786 non-whites in New Mexico, 229 of them were German; by 1860 there were 569 Germans in New Mexico (161). Beuthner went on to become postmaster (apparently in the Office of Superintendent of Indian Affairs) in 1855 (162) and a merchant banker in New Mexico (163). Beuthner became a member of the Masonic Lodge around 1854 (164). His brothers Joseph and Samson also came to Taos (164) and they had a mercantile business in Taos called Beuthner Brothers (established around 1860). Apparently their business was quite lucrative as Santa Fe merchant John Kingsbury reported in 1858 that “We have just got word from Taos that Samson Beuthner lost in one night $3000 + at billiards playing with Hicklin, and settled it next day by paying $1500+” (165).

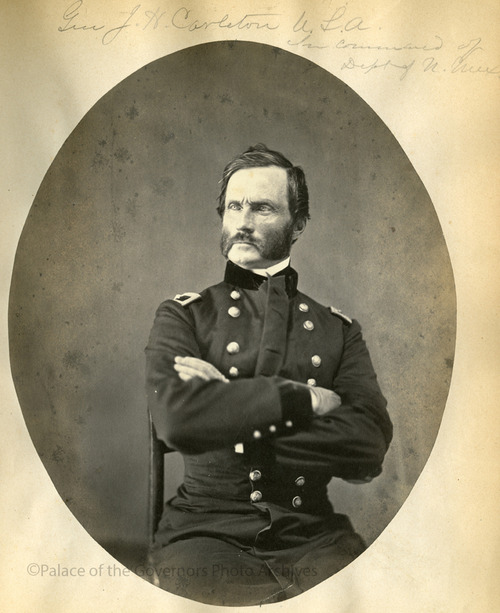

But from the following correspondence Beuthner had with General James H. Carleton, it may be that one of the lures for venturing into the northern frontier—gold—may also have been an incentive for him to purchase a house in Rio Colorado. In 1863 General James H. Carleton was notified by a trooper that “There is a report here that gold has been found in large quantities on Little Red River [this could be the Cimarron River, which was also known by this name]. I hope that is true. When the command returns I suppose that we shall learn all about it” (166). “I much hope that your mining shares will prove valuable as I have every reason to believe that the mines will prove to be very good. Your claims are located and recorded, and Mr. Solomon Beuthner would have sent them by this express but in fear that they might get wet or lost, he will bring them to you as soon as he visits Santa Fe” (167). Another letter refers to Carleton personally filing mining claims in New Mexico; he also contacted financiers in New York City to obtain capital to develop the mines.

A letter from Beuthner to Carleton dated November 27, 1863—

“I am exceedingly obliged to you, for the information contained in your letter, respecting the Gold Mines, and take this opportunity to assure you Dear Genl. that I shall use every effort to induce Men of Capital of this City [New York] to form Companies for the purpose of developing the vast resources of New Mexico, which I know is beyond the power of individuals to accomplish” (168).

Carleton encouraged his soldiers to look for mineral deposits throughout New Mexico and even encouraged people like Kit Carson to participate in these searches. Carson writes to Carleton in 1865 that “In regard to the new silver leads I am not sufficiently posted yet to say much about them but will advise you of the first favorable opportunity I hear of” (169). But Carleton is best known for supervising the removal of the Navajos from their lands during the 1863-1867 Long Walk to Bosque Redondo (170). Carleton makes clear his opinion of the Indians in an 1865 letter: “..the question which comes up, is, shall the miners be protected and the country developed, or shall the Indians be suffered to kill them and the nation be deprived of its immense wealth” (171)? For him it did not seem to be a question of protecting the frontier settlements.

A description of Rio Colorado at the end of the 1850s is provided by a traveling journalist Albert D. Richardson in his book Beyond the Mississippi (172). He describes the trail from Taos to Denver as a “…lonely mountain trail led through the range of the murderous Utes….” Miners coming south to New Mexico in the winter declared the trail “…as safe as Broadway. Others pronounced the journey madness, and its inevitable price a lost scalp.” Richardson obtained advice for the trip from Kit Carson in Taos and set off on October 25th with Carson, who stayed with him for the first hour of the trip. Richardson reached Rio Colorado the first night and gives the following description (173):

“After a solitary mountain ride of twenty-eight miles I dismounted at Beaubean’s trading-post beside a rushing transparent little stream bearing the name Colorado, so frequent in Spanish nomenclature. Beaubean was a Frenchman whom long intercourse with this mixed population had converted into a bewildered polyglot. With profuse bows and in a medley of French, German, Spanish, English, and Indian, he begged me to pardon his poor lodgings and his fare so unfit to set before a gentleman. As a sequel to this preamble he gave me a supper of mutton and eggs, the best meal I had eaten in New Mexico, served upon snowy linen, in a pleasant room. Then through the long evening I lounged in a luxurious arm-chair, reading before my cheerful fire with many glances through the skeleton window at tall snow-crowned mountains, with yawning black canyons between.”

“The dirt floor was smooth and hard. The mud walls, dressed with a trowel and whitewashed, could hardly be distinguised from the finest plastering. They were hung with pictures of saints, and crucifixes, curiously intermingled with views of horse races and cock fights. The mattress upon the floor, covered with fine blankets of whitest wool, was quite luxurious. That afternoon in a wretched hovel across the narrow street, a little child had fallen into the fire and had been burned to death. Now shrieks and moans rending the air, showed that in one dusky bosom under all its rags and wretchedness, the mother-heart was beating. Soon after the sunrise I rode on among scattered ranches with valley-fields of corn and wheat.”

Richardson then describes the crops he sees as he rides north out of Rio Colorado:

“Soon after sunrise I rode on among scattered ranches with valley-fields of corn and wheat. Irrigation makes the parched, sandy soil wonderfully productive. …It is not adapted to Indian corn on account of the cold nights. In winter farmers do not feed stock; the cattle subsist upon a wild sage so tall that it is seldom hidden by the snow.”

When Richardson reaches the Costilla River, he dines “…at the trading house of Mr. Posthoff, a German resident of gentlemanly manners and liberal culture….” He also describes a grist mill in Costilla—“…a horizontal water-wheel connected by an upright shaft with the millstone one story above. The stone, revolving no faster than the wheel, grinds very slowly, and having no bolting apparatus turns out very coarse flour.”

Note

155. Perkins, James E. Tom Tobin: Frontiersman. Herodotus Press, Pueblo West, CO, 1999.

156–157. LeCompte, Janet. “Charles Autobees.” In The Colorado Magazine XXXIV (Jul 1957), pp 163-180, (Oct 1957), pp 274-289; XXXV (Apr 1958) pp 139-153, (Oct 1958) pp 303-308; XXXVI (Jan 1959), pp 58-66, (Jul 1959) pp 202-213.

158. Lecompte, Janet. Charles Autobees. In LeRoy R Hafen, The Mountain Men and the Fur Trade of the Far West, volume 4, pp 21-37, The Arthur H. Clark Company, Glendale, CA, 1966.

159. Jones, Charles Irving. William Kroenig, New Mexico Pioneer. Part I, New Mexico Historical Review XIX, no. 3, July 1944, pp. 185-224; Part II, New Mexico Historical Review XIX, no. 4, October 1944, pp. 271-311.

160. Taos County Records, 1853-1869, Book A-1. Serial Number 16701, pp. 109-110. “John Baptiste Beaubien to Solomon Beuthner.’

161. Tobias, Henry J. A History of the Jews in New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1990

162. Treaty with Utes, September 11, 1855. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. www.yale. edu/lawweb/avalon/ntreaty/uta1855.htm, accessed 11/2/02.

163. Parish, William. Merchant Banking in Early New Mexico. Mid-Continent Banker 51(7); 1955, cited in Papers of Floyd S. Fierman, University of Arizona Library Manuscript Collection, SJA 003.

164 Tobias, Henry J. A History of the Jews in New Mexico. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1990, p 155.

165. Kingsbury, John M. Trading in Santa Fe: John M. Kingsbury’s correspondence with James Josiah Webb 1853-1861. Southern Methodist University Press, Dallas, TX, 1996. 166. NARA, RG 98, letters received, Need to Cutler, 29 September 1863, cited in Ackerly, Neal W. A Navajo diaspora: the long walk to Hweeldi. Dos Rio Consultants Inc., Silver City, NM, 1998.

166–171 Ackerly, Neal W. A Navajo diaspora: the long walk to Hweeldi. Dos Rio Consultants Inc., Silver City, NM, 1998. 167. NARA, RG 98, letters received, Need to Cutler, May 1, 1865, cited in Ackerly. 168. NARA, RG 98, letters received, Beuthner to Carleton, November 17, 1863, cited in Ackerly. 169. NARA, RG 98, letters received, Carson to Carleton, April 12, 1865, cited in Ackerly.

171. NARA, RG 98, letters received, Carleton to Doolittle, November 22, 1865, cited in Ackerly.

172–173. Richardson, Albert D. Beyond the Mississippi: From the Great River to the Great Ocean. Life and Adventure of the Prairies, Mountains, and Pacific Coast, 1857-1867. American Publishing Company, Hartford CT. National Publishing Company, Philadelphia, and Bliss & Company, New York 1867, pp. 269-275.