The arrival of the U.S. Military and the increased traffic on the Santa Fe Trail had served only to increase the anger of the Indians, and thus they stepped up their attacks on the frontier villages (134). Rio Colorado as the northernmost of the settlements bore the brunt of these attacks. The beleaguered citizens of Rio Colorado were offered some relief from Indian raids in the person of Lt. J.H. Whittlesey and his First Dragoons.

On March 9, 1849, Whittesley was ordered north to Rio Colorado to find the Utes that had been stealing the settlers’ livestock (135). The Utes had just lost a battle with the Arapahoes and needed food—they had told Col. Beall that they really had intended to pay for the cattle they had stolen.

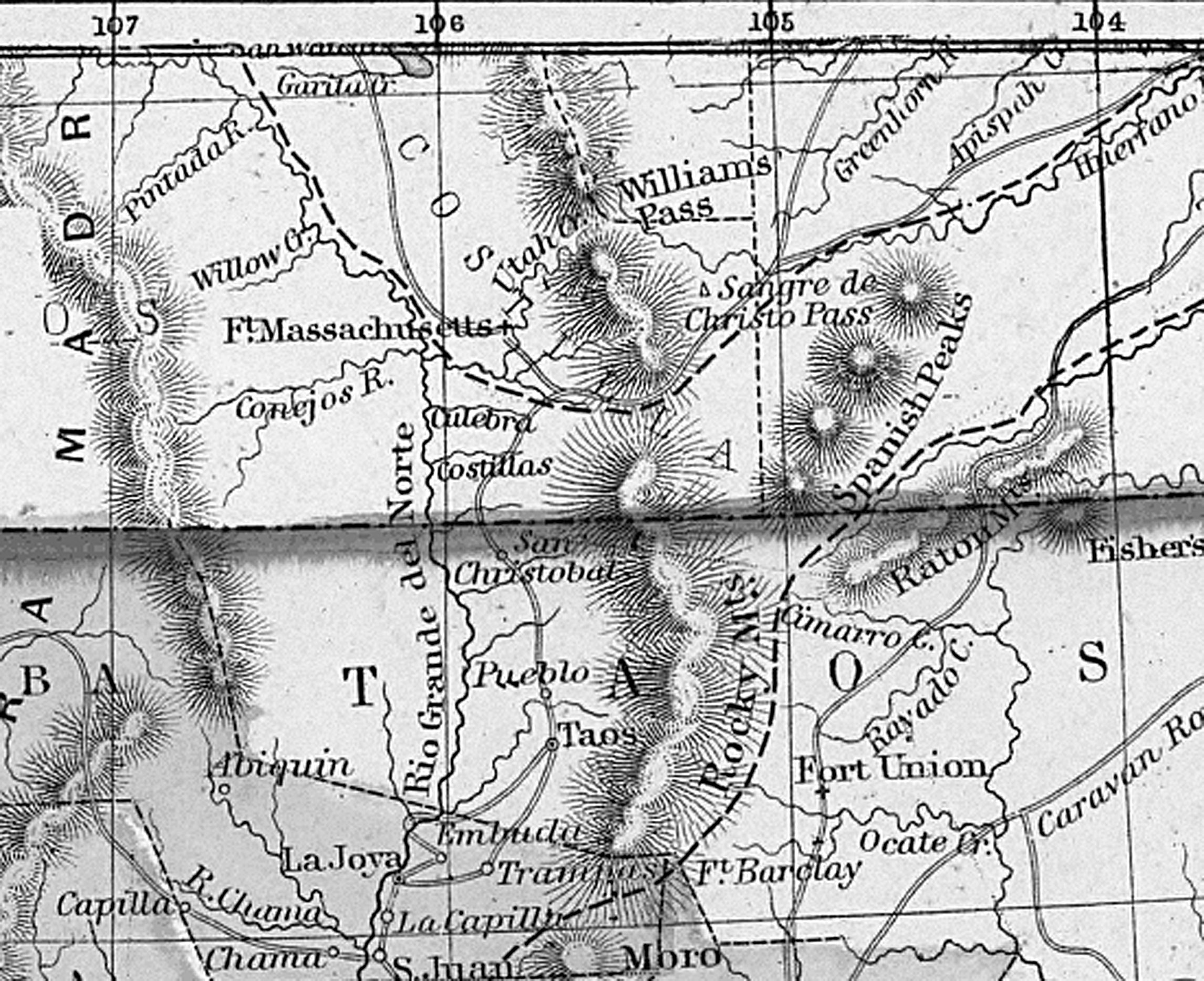

Whittlesley and his troops left Taos with 67 soldiers and a mountain howitzer on March 11 reached Rio Colorado on March 12. He chased the Utes out to near Cerro de Olla. Charles Autobees and his half-brother Tom Tobin went along with the troops as guides, as did trapper Antoine Leroux. The Lieutenant claims to have killed 10 Utes at the Battle of Cerro de Olla and to have wounded many more; he lost two of his troops and three horses. Whittlesley captured the Ute Chief Montoyo at Rio Colorado and brought him to Taos; Montoyo escaped from captivity there and was killed (136).

This campaign against the Utes would have further repercussions. Members of Fremont’s Fourth Expedition had returned to the area to retrieve supplies that had been cached in the mountains when the expedition foundered in the mountains to the north.

As described by Indian Agent John Greiner: “This expedition however well conducted was fatal to two Americans, who had started a few days previous to the arrival of command at Red River [Rio Colorado village] to open the ‘Cache’ made by Colonel Fremont at the head of the Rio Del Norte at the termination of his disastrous expedition. These men were Bill Williams, the celebrated trapper, and Doctor Kern, the physician and naturalist of Fremont’s party….. On their way back, when they were surrounded by a party of Utahs who had received the intelligence of Lt. Whittlesey’ s expedition, then taken prisoner and instantly killed….”

Library of Congress

The Utes had taken their revenge In February of 1850, James Calhoun, Indian Agent, and later first Territorial Governor of New Mexico, sent Auguste Lacome, a trader living in Arroyo Hondo, up to the Ute village north of Rio Colorado to see if they would negotiate a peace treaty (137). After some jurisdictional problems with Col. Benjamin Lloyd Beall, Lacome revisted these Mouache Utes and brought their answer to Governor Monroe—they did not want peace.

After New Mexico became a territory in 1850, the U.S. Government was unhappy about the high cost of troops in New Mexico (138). Col. E.V. Sumner was sent to the Taos region in 1851 to take care of the Indian problem cost effectively. His solution was to cancel all of the lucrative civilian contracts and build a series of frontier forts. Indian attacks increased, and the local New Mexicans became even more hostile toward the American government as the Indian troubles grew worse. By 1852, there were about 1000 soldiers in the entire New Mexico Territory, certainly not enough to control the continuing Indian depredations up and down the Rio Grande.

The army in 1850 was stationed at Rayado (squadron of Dragoons under Brevet Major Grier, 1st Dragoons) and at Don Fernandez de Taos (post established in 1847; there until 1852 when Fort Burgwin was established). George A. McCall, Inspector General in Taos describes the “inhabitants of the Valley of Taos are the most turbulent in New Mexico, and the Indians of the Pueblo of Taos, three and one-half miles north of Don Fernandez, still entertain a smothered feeling of animosity against the Americans, which it is well to keep under. But the force above specified is considered sufficient to enforce all police regulations and keep these people quiet” (139).

In an 1850 report, McCall reports 53 persons killed in Indian attacks on the northern frontier from September 1, 1848 to September 1, 1850, principally by Navajos, Utes, and Jicarilla Apaches. He also notes 13 captives taken from New Mexico. He also reports $114,050 worth of animals driven off by Indians during an 18-month period ending on September 1, 1850. Earlier, for the period 1846-1850, numbers of livestock taken by Indians are 12, 887 mules, 7050 horses, 31,581 cattle, 453,293 sheep (140)! But the northernmost point McCall was willing to recommend military protection was Taos.

The Indians were defended to some extent by people such as Col. George Archibald McCall, in his Report on Conditions in New Mexico (141): “The forays which the Apaches make upon the Mexicans are incited by want; they have nothing of their own and must plunder or starve. This is not the case with the Nabajoes. They have enriched themselves by appropriating the flocks and herds of an unresisting people and cannot offer the plea of necessity.” McCall described the Utes as numbering four or five thousand and that they did “…not extend their forays further south than Abiquiu, Taos, and Mora-town.” He added that “…they are often united with the Jicarilla Apaches.”

Slavery was also an issue. McCall (142) reported that a “New Mexican, living at San Miguel, recently returned from a large camp of Comanches and Apaches on the Pecos, stated that in the camp of the former there were almost as many Mexican slaves, women and children, as Indians. It will be a difficult matter to induce them to restore these prisoners. And until this unlicensed trade is broken up, their predatory incursions into New Mexico can never be checked.”

There were a series of treaties with the marauding tribes throughout the 1850s. A treaty was made with the Apaches on July 1, 1852, which stated in Article 5 that “Said nation, or tribe of Indians, do hereby bind themselves for future time to desist refrain from making any incursions within the Territory of New Mexico of a hostile or predatory character; and that they will for the future refrain from taking and conveying into captivity any of the people or citizens of Mexico, or the animals or property of the people or government of Mexico…” (143).

The Comanche, Kiowa, and Apache signed a similar treaty dated July 27, 1853, and the Mouhuache Utes signed one dated September 11, 1855. The Arapho and Cheyenne signed one dated October 14, 1865 and another dated October 21, 1867. However, none of these treaties seemed to stop the raids on Rio Colorado.

James S. Calhoun (144) in a letter of July 30th, 1850 reports a band of “Marches” [Mouache] Utes living 2 days north of Rio Colordao. Led by Ampariia, they had 20 lodges and about 40 warriors. Utes tell Col. Auguste Lacome that “…they were lords of that region—the whole country was theirs, not only the grass, wood and water, but the winds and sky above was theirs….” Calhoun estimated three warriors to a lodge. The Utes occuppied the west side of the mountains, and the Jicarillas the east side—their camp had 120 lodges.

In this same letter Calhoun also includes the following petition from citizens of Taos County, including several from Rio Colorado (144):

“To His Excellency, Governor Monroe , Military and Civil Governor of New Mexico.

The undersigned citizens of the County of Taos, would respectfully represent that the Apache Indians are within a days travel and but a few days ago entered the village of Rio Colorado, and are daily becoming bolder in their depredations. We therefore pray Your Excellency to issue an order for a campaign of the People of this County. The bearer of this petition [apparently Lacome] while [sic] explain the present whereabouts of these Indians, their feelings, &c as he has just returned from their village.

(Signed)

James H. Quinn

Lucien B. Maxwell

Thomas Birch

Wm. Krowing [sic; Kronig]

Wm. Becket

Francis Laforet

Choteau Laforet

Carlos Beaubien

Charles Ortebees [sic; Autobees]

Wm. White

Auguste Lacome

Jose Manuel Arrogon

Anto. Jose Valdez

Vital Truhillo

Phillipe Aragon

Jean Baptiste Charlefour

Anto. Laforet

Christopher Corson [sic; Carson, aka Kit Carson]”Note that several of the signers were residents of Rio Colorado and many of these names have already appeared in this text.

In a letter of February 26th 1850, Calhoun includes a report from Auguste Lacome of Arroyo Hondo that the Utes wish to make a permanent peace with the United States. They said they broke the previous Treaty at Abiqui because “…they were forced to do so from the fact, that they were in a starving condition, that when they robbed the ranches of the people of the northern part of the Territory, it was the purpose of the Chiefs subsequently to make reparation.” The Chiefs wanted to meet with Calhoun just north of Rio Colorado “…at a place called Costilla—about two days journey from Taos, or at the Sand Hills….” In a letter of March 29th 1850 Calhoun described the boundary between the Apaches and Utahs as commencing “…on the Rio del Norte, about latitute 37 degrees…” with the Jicarillas north of this line.

The policy of the government was made clear in a letter from H.N. Smith of the Office of Indian Affairs dated March 9th, 1850 (145):

“I do not think the Indians in and surrounding New Mexico are so lazy and indolent as the tribes nearer here and bordering upon our own civilization. After they are once reduced to a proper subjection and made to feel the Strength and power of our government and afterwards experience its clemency and kindness I am of opinion that they will prove to be very tractable, and under the guidance of discreet and worthy agents we may yet see some of their rich mountain valleys teeming with the produce of a laborious civilization. The Spaniards reclaimed from Savage life all our Pueblos and made them industrious and honest Cultivators of the soil, in a short time we might succeed as well with several of the wild tribes surrounding New Mexico.”

Another description of an Indian attack on Rio Colorado is included in a letter from John Greiner at Don Fernandez de Taos to Calhoun dated October 20th, 1851 (146):

“On the 4th instant a large party of Kiowa’s & Arrapahoes attacked a Eutaw village on the Lattira near Red River, about 30 miles from Taos, and drove off about 50 head of horses & mules and captured two women and four children.

On the 15th inst they made another attack upon the same Band within 18 miles of Taos on the opposite bank of the Rio Grande and drove off nearly all their remaining stock.

The Eutaws were forced to retreat to Ojo Caliente, where they are now uniting their forces in order to make a Campaign against these marauding Indians.

I know of no remedy to check these outrages. The Military force stationed here can afford no assistance. The post intended to be established in the Eutaw Country has—I learn—been abandoned until next Spring. The Eutaws are peaceable and kindly disposed towards our Citizens, and have behaved well.”

Regarding the settlement north of Rio Colorado, Greiner writes (147):

“…preparations are being made by Citizens of this Valley & others, to settle the lands claimed by the Eutaws in the Valley of the Los Conejos.

The Indians have repeatedly driven the Mexicans from this land—they say it is their Winter hunting ground that it contains the bones of their Fathers, and they cannot & will not give it up quietly.”

Troops were back in Rio Colorado in 1851, as described by J.A. Bennett. On March 11, 1851, Bennett was traveling with the Paymaster to Fort Massachusetts, north of Rio Colorado. They camped at Rio Colorado and Bennett described it as a settlement of 3000 inhabitants [surely an exaggeration!]—“the same as all others I have seen, indolent, dirty, immoral. Passed a restful night.” But he spread his scorn around and described Arroyo Hondo as “…the usual dirty and filthy place” (148). His diary is one of the first accounts of the military in New Mexico. But the views he expressed reflected the racial prejudices of his time. It is interesting that he had an entirely different attitude toward the local Indian populations, describing the Utes as “…fine, noble-looking Indians” and the Snakes “…like the Utahs, are rather friendly and manly with the Whites.”

This attitude apparently was an eastern one, as Territorial Governor Lew Wallace referred to it in a letter of about 1880 “So it is not strange if, in great bitterness of spirit, New Mexicans, without regard to class or nativity, are disposed to believe that the President reflects the sentimentalism of the which gentle folks on the banks of the Hudson and in the hearing of the bells of Cambridge are supposed best representatives. The latter are situated happily for the indulgence of rosecolored theories about the Indians…” (149). However, George D. Brewerton description of New Mexican women of the Taos area in his 1854 article about his travels in New Mexico (probably around 1848) is more charitable (149a).

“…the women of New Mexico toil harder…They are literally “hewers of wood and drawers of water;” but unlike their cowardly and treacherous lords, their hearts are ever open to the sufferings of the unfortunate. Many have borne witness to the fact; for the wounded mountaineer, the plundered trader, and fettered prisoners dragged as triumphal show through their villabes by men who never dared to meet their captives upon equal terms in the field, have experiences sympathy and obtained relief from those dark-eyed daughters of New Mexico.”

His view of the Taos-area men was quite the opposite—“Sleeping, smoking, and gambling consume the greater portion of their day; while nightly fandangoes furnish fruitful occasions for murder, robbery, and other acts of outrage,”

After moving troops back and forth from Taos to the San Luis Valley, in 1852 the Army established Fort Massachusetts 80 miles north of Taos and Fort Burgwin southwest of Taos to protect Taos and the Rio Colorado frontier against the Indian depredations and to protect against another Mexican rebellion (150).

The U.S. Government finally took effective military action in 1855 after the December 25, 1854 massacre of the inhabitants of Fort Pueblo led by the Ute chief Tierra Blanco. Five mounted companies of volunteer troops were called up in January 1855 to put down the Utes and they set out for Fort Massachusetts near Mount Blanca. They then moved north to confront the Utes, and by April 30th, Tierra Blanco was asking for peace. They again appealed for peace in June and were escorted to Abiquiu where an agreement was reached on September 10th with the Utes and the Jicarilla Apaches.

Kit Carson reported after this meeting that “The Indians that are now committing depredations are those who have lost their families during the war. They consider they have nothing further to live for than revenge for the death of those of their families that were killed by the whites; they have become desperate; when they will ask for peace I can not say” (151). Unfortunately, the U.S. Senate dragged its collective feet for many years in ratifying the treaties and it was not until 1863 that a new treaty with the Utes was ratified by the Senate. In the meantime, Rio Colorado continued to suffer from raids from these very tribes.

Although the U.S. Army was stationed at Taos and at Rayado, the Rio Colorado settlers continued to be plagued by Indian attacks. The Taos County Register of Strays (1856–1899) (152) records some of the losses. From a March 11, 1857 raid, Justice of the Peace of Rio Colorado Jose Miguel Ortiz claims the loss of five beasts of burden and one mule to Apaches and Jicarillas. The Indians, identified as Yutas, also killed a cow in this raid.

In a December 29, 1861, raid, Indians made off with three cows and one bull from Juan Nepromoseno Bargas, one bull from Francisco Suaso, two cows from Francisco Martin, one cow from Desiderio Valdez, 20 of Jose Maria Martinez’ goats, and 79 sheep and 32 wagons. Then on January 5, 1862, the raiders were back to take sheep, livestock, and fruit. A September 6, 1862 raid on Rio Colorado by Utes and Apaches netted 16 horses, 7 wagons, and 23 sheep.

The U.S. Government was supposed to make good on property lost in such raids. The Congressional Records of the time are littered with accounts of Indians depredations and requests for indemnities and with bills “providing for the examination of claims of Indian depredations in the Territory of New Mexico.”

The 34th Congress of 1856 authorized the Secretary of the Interior “to cause an investigation to be had of the claims for depredations by Indians in the Territory of New Mexico, that may have been heretofore made and filed in the Department of the Interior, and report to the next session of Congress, or as soon as practicable, the facts in each case, and particularly enumerating such as come within the provisions of the intercourse law, and for which in his opinion indemnity should be provided by Congress: Provided, That nothing herein contained should be construed to bind the United States to make payment of said claims.” By 1869, the residents were petitioning the Congress and “praying for protection against the depredations of the Indians.” In 1874 a bill “for the relief of certain persons in New Mexico, for Indian depredations” was presented to House of Representatives (153).

Whether the residents of Rio Colorado ever received any compensation for their claims is a matter for further research and investigation. In 1859, a speech made by NM representative M.A. Otero in the House of Representatives stated that there had been no action on citizens’ claims for Indian depredations (154). “When I first came to Congress, I found that many claims were filed in the Interior Department with regard to Indian depredations from New Mexico. No action had been taken upon them up to that time.” Otero had been instrumental in passing the legislation quoted above in the 34th Congress, but as of 1859 Congress would not act—“I have ever since labored to bring the subject before Congress for its action.”

He goes on to say “We had hoped, when you took possession of that Territory, that all our troubles were at an end; but we seem to have been doomed to bitter disappointment. Our property has been stolen; our people have been violated and murdered, and our children taken into captivity; …You cannot visit a village or a hamlet in the entire Territory but you hear the sad tales of murdered friends and relatives…..the people of New Mexico complain that the protection that was promised has not been extended to them; and that having failed in that, they ask for something that might be done to have their claims for Indian depredations examined….”

And finally in Otero there is a spokesman for the good character of the Spanish population— “The people of that Territory are Mexican born, but the great majority of Castilian origin and descent, and are generous, noble, and brave; and in a striking degree they retain the elements of their Spanish extraction; native quickness of perception and apprehension, pride of character, love of adventure, generosity of impulse, and a characteristic heedlessness of personal danger. They are a people possessing, in an eminent degree, moral probity and integrity in all transactions of business—are active, energetic, and enterprising. Their perservering traders have been, sir, the pioneers, the creators, and the establishers of that vast inland traffic which now animates the boundless prairies into green seas that grandly swell with accumulating floods of thriving commerce.”’

Note

134. LeCompte, Janet. “Charles Autobees.” In The Colorado Magazine XXXIV (Jul 1957), pp 163-180, (Oct 1957), pp 274-289; XXXV (Apr 1958) pp 139-153, (Oct 1958) pp 303-308; XXXVI (Jan 1959), pp 58-66, (Jul 1959) pp 202-213.

135. Perkins, James E. Tom Tobin: Frontiersman. Herodotus Press, Pueblo West, CO, 1999.

136. Richmond, Patricia Joy. Trail to Disaster: The Route of John C. Fremont’s Fourth Expedition from Big Timbers, Colorado, through the San Luis Valley, to Taos, New Mexico. University Press of Colorado, Colorado Historical Society, Denver, CO, 1989, 1990

136. U.S. Congress, Senate Executive Documents 24, 11-13.

137. Abel, Annie H. (ed.). The Official Correspondence of James A. Calhoun while agent at Santa Fe and Superintendant of Indian Affairs in New Mexico. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1915; Office of Indian Affairs. The Official Correspondence of James S. Calhoun while Indian agent at Santa Fe and superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, collected from the files of the Indian Office and edited under its direction, by Annie Heloise Abel. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1915.

138. LeCompte, Janet. “Charles Autobees.” In The Colorado Magazine XXXIV (Jul 1957), pp 163- 180, (Oct 1957), pp 274-289; XXXV (Apr 1958) pp 139-153, (Oct 1958) pp 303-308; XXXVI (Jan 1959), pp 58-66, (Jul 1959) pp 202-213.

138-142. McCall, Col. George Archibald. New Mexico in 1850: A Military View. Robert W. Frazier (ed.). University of Oklahoma Press, Norman.

139. Murphy, Lawrence R. The United Staters Army in Taos, 1847-1852, New Mexico Historical Review XLVIII, no. 1, January 1972, pp. 33-48; also see Bender 1934; Murphy 1972.

143. Treaty with the Apache, July 1, 1852. The Avalon Project at Yale Law School. www.yale.edu/ lawweb/avalon/ntreaty/apa1852.htm, accessed 11/2/02.

144–147. Office of Indian Affairs. The Official Correspondence of James S. Calhoun while Indian agent at Santa Fe and superintendent of Indian affairs in New Mexico, collected from the files of the Indian Office and edited under its direction, by Annie Heloise Abel. Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1915.

148. Bennett, James A. Forts and Forays: A Dragoon in New Mexico 1850-1856. C.E. Brooks and F.D. Reeve, eds. University of New Mexico Press, Albuquerque, 1948, 1966.

149. Horn, Calvin. New Mexico’s Troubled Years: The Story of the Early Territorial Governors. Horn & Wallace Publishers, Albuquerque, 1963.

149a. Brewerton, G. Douglass. Incidents of travel in New Mexico. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine VIII(47), April 1854. Memory.loc.gov, accessed 8/5/02.

150. Murphy, Lawrence R. The United States Army in Taos, 1847–1852, New Mexico Historical Review XLVIII, no. 1, January 1972, pp. 33-48.

151. Time event chart of the San Luis Valley. The San Luis Valley Historian 1(2), 4-5, 1969.

152. Taos County Records. Indian Depredations 1856-1889, Register of Strays 1858-1899. Box 16757. New Mexico State Center for Records and Archives.

153 .Century of Lawmaking, U.S. Congression Documents and Debates, 1774-1873, Statutes at Large, 34th Congress, 1st session, 1856. Memory.loc.gov,a ccessed 9/28/02.

154. Speech of Hon. M.A. Otero. Congressional Globe, House of Representatives, 35th Congress, 2nd session, February 21, 1859. Memory.loc.gov, accessed 9/28/02.